Transducers: Efficient Data Processing Pipelines in JavaScript

Prior to taking on transducers, you should first have a strong understanding of both function composition and reducers.

Transduce: Derived from the 17th century scientific latin, “transductionem” means “to change over, convert”. It is further derived from “transducere/traducere”, which means “to lead along or across, transfer”.

A transducer is a composable higher-order reducer. It takes a reducer as input, and returns another reducer.

Transducers are:

- Composable using simple function composition

- Efficient for large collections with multiple operations: Only enumerates over the collection once, regardless of the number of operations in the pipeline

- Able to transduce over any enumerable source (e.g., arrays, trees, streams, graphs, etc…)

- Usable for either lazy or eager evaluation with no changes to the transducer pipeline

Reducers fold multiple inputs into single outputs, where “fold” can be replaced with virtually any binary operation that produces a single output, such as:

// Sums: (1, 2) = 3

const add = (a, c) => a + c // Products: (2, 4) = 8

const multiply = (a, c) => a * c // String concatenation: ('abc', '123') = 'abc123'

const concatString = (a, c) => a + c // Array concatenation: ([1,2], [3,4]) = [1, 2, 3, 4]

const concatArray = (a, c) => [...a, ...c]

Transducers do much the same thing, but unlike ordinary reducers, transducers are composable using normal function composition. In other words, you can combine any number of transducers to form a new transducer which links each component transducer together in series.

Normal reducers can’t compose, because they expect two arguments, and only return a single output value, so you can’t simply connect the output to the input of the next reducer in the series. The types don’t line up:

f: (a, c) => a

g: (a, c) => a

h: ???

Transducers have a different signature:

f: reducer => reducer

g: reducer => reducer

h: reducer => reducer

Why Transducers?

Often, when we process data, it’s useful to break up the processing into multiple independent, composable stages. For example, it’s very common to select some data from a larger set, and then process that data. You may be tempted to do something like this:

const friends = [

{ id: 1, name: "Sting", nearMe: true },

{ id: 2, name: "Radiohead", nearMe: true },

{ id: 3, name: "NIN", nearMe: false },

{ id: 4, name: "Echo", nearMe: true },

{ id: 5, name: "Zeppelin", nearMe: false },

]

const isNearMe = ({ nearMe }) => nearMe

const getName = ({ name }) => name

const results = friends.filter(isNearMe).map(getName)

console.log(results)

// => ["Sting", "Radiohead", "Echo"]

This is fine for small lists like this, but there are some potential problems:

- This only works for arrays. What about potentially infinite streams of data coming in from a network subscription, or a social graph with friends-of-friends?

- Each time you use the dot chaining syntax on an array, JavaScript builds up a whole new intermediate array before moving onto the next operation in the chain. If you have a list of 2,000,000 “friends” to wade through, that could slow things down by an order of magnitude or two. With transducers, you can stream each friend through the complete pipeline without building up intermediate collections between them, saving lots of time and memory churn.

- With dot chaining, you have to build different implementations of standard operations, like

.filter(),.map(),.reduce(),.concat(), and so on. The array methods are built into JavaScript, but what if you want to build a custom data type and support a bunch of standard operations without writing them all from scratch? Transducers can potentially work with any transport data type: Write an operator once, use it anywhere that supports transducers.

Let’s see what this would look like with transducers. This code won’t work yet, but follow along, and you’ll be able to build every piece of this transducer pipeline yourself:

const friends = [

{ id: 1, name: "Sting", nearMe: true },

{ id: 2, name: "Radiohead", nearMe: true },

{ id: 3, name: "NIN", nearMe: false },

{ id: 4, name: "Echo", nearMe: true },

{ id: 5, name: "Zeppelin", nearMe: false },

]

const isNearMe = ({ nearMe }) => nearMe

const getName = ({ name }) => name

const getFriendsNearMe = compose(filter(isNearMe), map(getName))

const results2 = toArray(getFriendsNearMe, friends)

Transducers don’t do anything until you tell them to start and feed them some data to process, which is why we need toArray(). It supplies the transducible process and tells the transducer to transduce the results into a new array. You could tell it to transduce to a stream, or an observable, or anything you like, instead of calling toArray().

A transducer could map numbers to strings, or objects to arrays, or arrays to smaller arrays, or not change anything at all, mapping { x, y, z } -> { x, y, z }. Transducers may also filter parts of the signal out of the stream { x, y, z } -> { x, y }, or even generate new values to insert into the output stream, { x, y, z } -> { x, xx, y, yy, z, zz }.

I will use the words “signal” and “stream” somewhat interchangeably in this section. Keep in mind when I say “stream”, I’m not referring to any specific data type: simply a sequence of zero or more values, or a list of values expressed over time.

Background and Etymology

In hardware signal processing systems, a transducer is a device which converts one form of energy to another, e.g., audio waves to electrical, as in a microphone transducer. In other words, it transforms one kind of signal into another kind of signal. Likewise, a transducer in code converts from one signal to another signal.

Use of the word “transducers” and the general concept of composable pipelines of data transformations in software date back at least to the 1960s, but our ideas about how they should work have changed from one language and context to the next. Many software engineers in the early days of computer science were also electrical engineers. The general study of computer science in those days often dealt both with hardware and software design. Hence, thinking of computational processes as “transducers” was not particularly novel. It’s possible to encounter the term in early computer science literature — particularly in the context of Digital Signal Processing (DSP) and data flow programming.

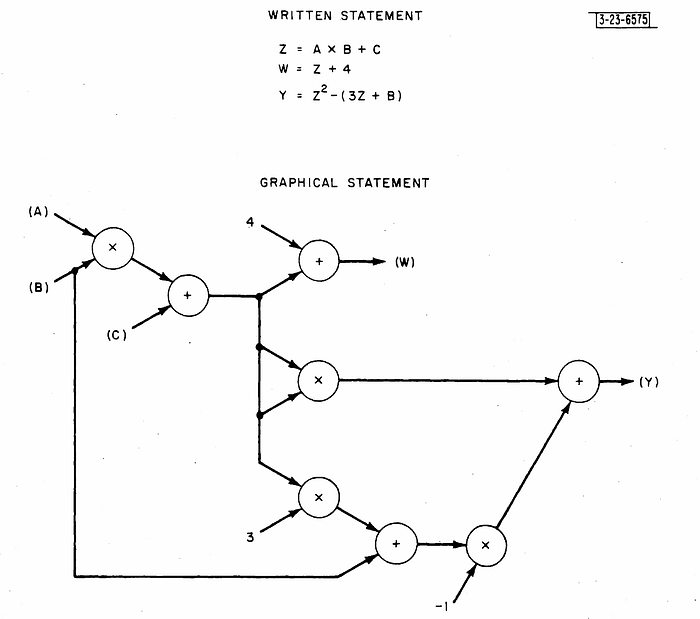

In the 1960s, groundbreaking work was happening in graphical computing in MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory using the TX-2 computer system, a precursor to the US Air Force SAGE defense system. Ivan Sutherland’s famous Sketchpad, developed in 1961–1962, was an early example of object prototype delegation and graphical programming using a light pen.

Ivan’s brother, William Robert “Bert” Sutherland was one of several pioneers in data flow programming. He built a data flow programming environment on top of Sketchpad, which described software “procedures” as directed graphs of operator nodes with outputs linked to the inputs of other nodes. He wrote about the experience in his 1966 paper, “The On-Line Graphical Specification of Computer Procedures”. Instead of arrays and array processing, everything is represented as a stream of values in a continuously running, interactive program loop. Each value is processed by each node as it arrives at the parameter input. You can find similar systems today in Unreal Engine’s Blueprints Visual Scripting Environment or Native Instruments’ Reaktor, a visual programming environment used by musicians to build custom audio synthesizers.

Composed graph of operators from Bert Sutherland’s paper

As far as I’m aware, the first book to popularize the term “transducer” in the context of general purpose software-based stream processing was the 1985 MIT text book for a computer science course called “Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs” (SICP) by Harold Abelson and Gerald Jay Sussman, with Julie Sussman. However, the use of the term “transducer” in the context of digital signal processing predates SICP.

Note: SICP is still an excellent introduction to computer science coming from a functional programming perspective. It remains my favorite book on the topic.

More recently, transducers have been independently rediscovered and a different protocol developed for Clojure by Rich Hickey (circa 2014), who is famous for carefully selecting words for concepts based on etymology. In this case, I’d say he nailed it, because Clojure transducers fill almost exactly the same niche as transducers in SICP, and they share many common characteristics. However, they are not strictly the same thing.

Transducers as a general concept (not specifically Hickey’s protocol specification) have had considerable impact on important branches of computer science including data flow programming, signal processing for scientific and media applications, networking, artificial intelligence, etc. As we develop better tools and techniques to express transducers in our application code, they are beginning to help us make better sense of every kind of software composition, including user interface behaviors in web and mobile apps, and in the future, could also serve us well to help manage the complexity of augmented reality, autonomous devices and vehicles, etc.

For the purpose of this discussion, when I say “transducer”, I’m not referring to SICP transducers, though it may sound like I’m describing them if you’re already familiar with transducers from SICP. I’m also not referring specifically to Clojure’s transducers, or the transducer protocol that has become a de facto standard in JavaScript (supported by Ramda, Transducers-JS, RxJS, etc…). I’m referring to the general concept of a higher-order reducer — a transformation of a transformation.

In my view, the particular details of the transducer protocols matter a whole lot less than the general principles and underlying mathematical properties of transducers, however, if you want to use transducers in production, my current recommendation is to use an existing library which implements the transducers protocol for interoperability reasons.

The transducers that I will describe here should be considered pseudo-code to express the concepts. They are not compatible with the transducer protocol, and should not be used in production. If you want to learn how to use a particular library’s transducers, refer to the library documentation. I’m writing them this way to lift up the hood and let you see how they work without forcing you to learn the protocol at the same time.

When we’re done, you should have a better understanding of transducers in general, and how you might apply them in any context, with any library, in any language that supports closures and higher-order functions.

A Musical Analogy for Transducers

If you’re among the large number of software developers who are also musicians, a music analogy may be useful: You can think of transducers like signal processing gear (e.g., guitar distortion pedals, EQ, volume knobs, echo, reverb, and audio mixers).

To record a song using musical instruments, we need some sort of physical transducer (i.e., a microphone) to convert the sound waves in the air into electricity on the wire. Then we need to route that wire to whatever signal processing units we’d like to use. For example, adding distortion to an electric guitar, or reverb to a voice track. Eventually this collection of different sounds must be aggregated together and mixed to form a single signal (or collection of channels) representing the final recording.

In other words, the signal flow might look something like this. Imagine the arrows are wires between transducers:

[ Source ] -> [ Mic ] -> [ Filter ] -> [ Mixer ] -> [ Recording ]

In more general terms, you could express it like this:

[ Enumerator ]->[ Transducer ]->[ Transducer ]->[ Accumulator ]

If you’ve ever used music production software, this might remind you of a chain of audio effects. That’s a good intuition to have when you’re thinking about transducers, but they can be applied much more generally to numbers, objects, animation frames, 3d models, or anything else you can represent in software.

Screenshot: Renoise audio effects channel

You may be experienced with something that behaves a little bit like a transducer if you’ve ever used the map method on arrays. For example, to double a series of numbers:

const double = (x) => x * 2

const arr = [1, 2, 3]

const result = arr.map(double)

In this example, the array is an enumerable object. The map method enumerates over the original array, and passes its elements through the processing stage, double, which multiplies each element by 2, then accumulates the results into a new array.

You can even compose effects like this:

const double = (x) => x * 2

const isEven = (x) => x % 2 === 0

const arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

const result = arr.filter(isEven).map(double)

console.log(result)

// [4, 8, 12]

But what if you want to filter and double a potentially infinite stream of numbers, such as a drone’s telemetry data?

Arrays can’t be infinite, and each stage in the array processing requires you to process the entire array before a single value can flow through the next stage in the pipeline. That same limitation means that composition using array methods will have degraded performance because a new array will need to be created and a new collection iterated over for each stage in the composition.

Imagine you have two sections of tubing, each of which represents a transformation to be applied to the data stream, and a string representing the stream. The first transformation represents the isEven filter, and the next represents the double map. In order to produce a single fully transformed value from an array, you'd have to run the entire string through the first tube first, resulting in a completely new, filtered array before you can process even a single value through the double tube. When you finally do get to double your first value, you have to wait for the entire array to be doubled before you can read a single result.

So, the code above is equivalent to this:

const double = (x) => x * 2

const isEven = (x) => x % 2 === 0

const arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

const tempResult = arr.filter(isEven)

const result = tempResult.map(double)

console.log(result)

// [4, 8, 12]

The alternative is to flow a value directly from the filtered output to the mapping transformation without creating and iterating over a new, temporary array in between. Flowing the values through one at a time removes the need to iterate over the same collection for each stage in the transducing process, and transducers can signal a stop at any time, meaning you don’t need to enumerate each stage deeper over the collection than required to produce the desired values.

There are two ways to do that:

- Pull: lazy evaluation, or

- Push: eager evaluation

A pull API waits until a consumer asks for the next value. A good example in JavaScript is an Iterable, such as the object produced by a generator function. Nothing happens in the generator function until you ask for the next value by calling .next()on the iterator object it returns.

A push API enumerates over the source values and pushes them through the tubes as fast as it can. A call to array.reduce() is a good example of a push API. array.reduce() takes one value at a time from the array and pushes it through the reducer, resulting in a new value at the other end. For eager processes like array reduce, the process is immediately repeated for each element in the array until the entire array has been processed, blocking further program execution in the meantime.

Transducers don’t care whether you pull or push. Transducers have no awareness of the data structure they’re acting on. They simply call the reducer you pass into them to accumulate new values.

Transducers are higher order reducers: Reducer functions that take a reducer and return a new reducer. Rich Hickey describes transducers as process transformations, meaning that as opposed to simply changing the values flowing through transducers, transducers change the processes that act on those values.

The signatures look like this:

reducer = (accumulator, current) => accumulator

transducer = (reducer) => reducer

Or, to spell it out:

transducer = ((accumulator, current) => accumulator) => ((accumulator, current) => accumulator)

Generally speaking though, most transducers will need to be partially applied to some arguments to specialize them. For example, a map transducer might look like this:

map = (transform) => (reducer) => reducer

Or more specifically:

map = (a => b) => step => reducer

In other words, a map transducer takes a mapping function (called a transform) and a reducer (called the step function), and returns a new reducer. The step function is a reducer to call when we've produced a new value to add to the accumulator in the next step.

Let’s look at some naive examples:

const compose =

(...fns) =>

(x) =>

fns.reduceRight((y, f) => f(y), x)

const map = (f) => (step) => (a, c) => step(a, f(c))

const filter = (predicate) => (step) => (a, c) => predicate(c) ? step(a, c) : a

const isEven = (n) => n % 2 === 0

const double = (n) => n * 2

const doubleEvens = compose(filter(isEven), map(double))

const arrayConcat = (a, c) => a.concat([c])

const xform = doubleEvens(arrayConcat)

const result = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6].reduce(xform, []) // [4, 8, 12]

console.log(result)

That’s a lot to absorb. Let’s break it down. map applies a function to the values inside some context. In this case, the context is the transducer pipeline. It looks roughly like this:

const map = (f) => (step) => (a, c) => step(a, f(c))

You can use it like this:

const double = (x) => x * 2

const doubleMap = map(double)

const step = (a, c) => console.log(c)

doubleMap(step)(0, 4) // 8

doubleMap(step)(0, 21) // 42

The zeros in the function calls at the end represent the initial values for the reducers. Note that the step function is supposed to be a reducer, but for demonstration purposes, we can hijack it and log to the console. You can use the same trick in your unit tests if you need to make assertions about how the step function gets used.

Transducers get interesting when we compose them together. Let’s implement a simplified filter transducer:

const filter = (predicate) => (step) => (a, c) => predicate(c) ? step(a, c) : a

Filter takes a predicate function and only passes through the values that match the predicate. Otherwise, the returned reducer returns the accumulator, unchanged.

Since both of these functions take a reducer and return a reducer, we can compose them with simple function composition:

const compose =

(...fns) =>

(x) =>

fns.reduceRight((y, f) => f(y), x)

const isEven = (n) => n % 2 === 0

const double = (n) => n * 2

const doubleEvens = compose(filter(isEven), map(double))

This will also return a transducer, which means we must supply a final step function in order to tell the transducer how to accumulate the result:

const arrayConcat = (a, c) => a.concat([c])

const xform = doubleEvens(arrayConcat)

The result of this call is a standard reducer that we can pass directly to any compatible reduce API. The second argument represents the initial value of the reduction. In this case, an empty array:

const result = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6].reduce(xform, []) // [4, 8, 12]

If this seems like a lot of work, keep in mind there are already functional programming libraries that supply common transducers along with utilities such as compose, which handles function composition, and into, which transduces a value into the given empty value, e.g.:

const xform = compose(map(inc), filter(isEven))

into([], xform, [1, 2, 3, 4]) // [2, 4]

With most of the required tools already in the tool belt, programming with transducers is really intuitive.

Some popular libraries which support transducers include Ramda, RxJS, and Mori.

Transducers Compose Top-to-Bottom

Transducers under standard function composition (f(g(x))) apply top to bottom/left-to-right rather than bottom-to-top/right-to-left. In other words, using normal function composition, compose(f, g) means "compose f after g". Transducers wrap around other transducers under composition. In other words, a transducer says "I'm going to do my thing, and then call the next transducer in the pipeline", which has the effect of turning the execution stack inside out.

Imagine you have a stack of papers, the top labeled, f, the next, g, and the next h. For each sheet, take the sheet off the top of the stack and place it onto the top of a new adjacent stack. When you're done, you'll have a stack whose sheets are labeled h, then g, then f.

Transducer Rules

The examples above are naive because they ignore the rules that transducers must follow for interoperability.

As with most things in software, transducers and transducing processes need to obey some rules:

- Initialization: Given no initial accumulator value, a transducer must call the step function to produce a valid initial value to act on. The value should represent the empty state. For example, an accumulator that accumulates an array should supply an empty array when its step function is called with no arguments.

- Early termination: A process that uses transducers must check for and stop when it receives a reduced accumulator value. Additionally, a transducer step function that uses a nested reduce must check for and convey reduced values when they are encountered.

- Completion (optional): Some transducing processes never complete, but those that do should call the completion function to produce a final value and/or flush state, and stateful transducers should supply a completion operation that cleans up any accumulated resources and potentially produces one final value.

Initialization

Let’s go back to the map operation and make sure that it obeys the initialization (empty) law. Of course, we don't need to do anything special, just pass the request down the pipeline using the step function to create a default value:

const map =

(f) =>

(step) =>

(a = step(), c) =>

step(a, f(c))

The part we care about is a = step() in the function signature. If there is no value for a (the accumulator), we'll create one by asking the next reducer in the chain to produce it. Eventually, it will reach the end of the pipeline and (hopefully) create a valid initial value for us.

Remember this rule: When called with no arguments, a reducer should always return a valid initial (empty) value for the reduction. It’s generally a good idea to obey this rule for any reducer function, including reducers for React or Redux.

Early Termination

It’s possible to signal to other transducers in the pipeline that we’re done reducing, and they should not expect to process any more values. Upon seeing a reduced value, other transducers may decide to stop adding to the collection, and the transducing process (as controlled by the final step() function) may decide to stop enumerating over values. The transducing process may make one more call as a result of receiving a reduced value: The completion call mentioned above. We can signal that intention with a special reduced accumulator value.

What is a reduced value? It could be as simple as wrapping the accumulator value in a special type called reduced. Think of it like wrapping a package in a box and labelling the box with messages like "Express" or "Fragile". Metadata wrappers like this are common in computing. For example: http messages are wrapped in containers called "request" or "response", and those container types have headers that supply information like status codes, expected message length, authorization parameters, etc...

Basically, it’s a way of sending multiple messages where only a single value is expected. A minimal (non-standard) example of a reduced() type lift might look like this:

const reduced = (v) => ({

get isReduced() {

return true

},

valueOf: () => v,

toString: () => `Reduced(${JSON.stringify(v)})`,

})

The only parts that are strictly required are:

- The type lift: A way to get the value inside the type (e.g., the

reducedfunction, in this case) - Type identification: A way to test the value to see if it is a value of

reduced(e.g., theisReducedgetter) - Value extraction: A way to get the value back out of the type (e.g.,

valueOf())

toString() is included here strictly for debugging convenience. It lets you introspect both the type and the value at the same time in the console.

Completion

“In the completion step, a transducer with reduction state should flush state prior to calling the nested transformer’s completion function, unless it has previously seen a reduced value from the nested step in which case pending state should be discarded.” ~ Clojure transducers documentation

In other words, if you have more state to flush after the previous function has signaled that it’s finished reducing, the completion step is the time to handle it. At this stage, you can optionally:

- Send one more value (flush your pending state)

- Discard your pending state

- Perform any required state cleanup

Transducing

It’s possible to transduce over lots of different types of data, but the process can be generalized:

// import a standard curry, or use this magic spell:

const curry =

(f, arr = []) =>

(...args) =>

((a) => (a.length === f.length ? f(...a) : curry(f, a)))([...arr, ...args])

const transduce = curry((step, initial, xform, foldable) =>

foldable.reduce(xform(step), initial)

)

The transduce() function takes a step function (the final step in the transducer pipeline), an initial value for the accumulator, a transducer, and a foldable. A foldable is any object that supplies a .reduce() method.

With transduce() defined, we can easily create a function that transduces to an array. First, we need a reducer that reduces to an array:

const concatArray = (a, c) => a.concat([c])

Now we can use the curried transduce() to create a partial application that transduces to arrays:

const toArray = transduce(concatArray, [])

With toArray() we can replace two lines of code with one, and reuse it in a lot of other situations, besides:

// Manual transduce:

const xform = doubleEvens(arrayConcat)

const result = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6].reduce(xform, [])

// => [4, 8, 12]// Automatic transduce:

const result2 = toArray(doubleEvens, [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6])

console.log(result2) // [4, 8, 12]

The Transducer Protocol

Up to this point, I’ve been hiding some details behind a curtain, but it’s time to take a look at them now. Transducers are not really a single function. They’re made from 3 different functions. Clojure switches between them using pattern matching on the function’s arity.

In computer science, the arity of a function is the number of arguments a function takes. In the case of transducers, there are two arguments to the reducer function, the accumulator and the current value. In Clojure, Both are optional, and the behavior changes based on whether or not the arguments get passed. If a parameter is not passed, the type of that parameter inside the function is undefined.

The JavaScript transducer protocol handles things a little differently. Instead of using function arity, JavaScript transducers are a function that take a transducer and return a transducer. The transducer is an object with three methods:

initReturn a valid initial value for the accumulator (usually, just call the nextstep()).stepApply the transform, e.g., formap(f):step(accumulator, f(current)).resultIf a transducer is called without a new value, it should handle its completion step (usuallystep(a), unless the transducer is stateful).

Note: The transducer protocol in JavaScript uses

@@transducer/init,_@@transducer/step_, and_@@transducer/result_, respectively.

Some libraries provide a transducer() utility that will automatically wrap your transducer for you.

Here is a less naive implementation of the map transducer:

const map = (f) => (next) =>

transducer({

init: () => next.init(),

result: (a) => next.result(a),

step: (a, c) => next.step(a, f(c)),

})

By default, most transducers should pass the init() call to the next transducer in the pipeline, because we don't know the transport data type, so we can't produce a valid initial value for it.

Additionally, the special reduced object uses these properties (also namespaced @@transducer/<name> in the transducer protocol:

reducedA boolean value that is alwaystruefor reduced values.valueThe reduced value.

Conclusion

Transducers are composable higher order reducers which can reduce over any underlying data type.

Transducers produce code that can be orders of magnitude more efficient than dot chaining with arrays, and handle potentially infinite data sets without creating intermediate aggregations.

Note: Transducers aren’t always faster than built-in array methods. The performance benefits tend to kick in when the data set is very large (hundreds of thousands of items), or pipelines are quite large (adding significantly to the number of iterations required using method chains). If you’re after the performance benefits, remember to profile.

Take another look at the example from the introduction. You should be able to build filter(), map(), and toArray() using the example code as a reference and make this code work:

const friends = [

{ id: 1, name: "Sting", nearMe: true },

{ id: 2, name: "Radiohead", nearMe: true },

{ id: 3, name: "NIN", nearMe: false },

{ id: 4, name: "Echo", nearMe: true },

{ id: 5, name: "Zeppelin", nearMe: false },

]

const isNearMe = ({ nearMe }) => nearMe

const getName = ({ name }) => name

const getFriendsNearMe = compose(filter(isNearMe), map(getName))

const results2 = toArray(getFriendsNearMe, friends)

In production, you can use transducers from RxJS or Ramda. In real code, I usually reach for transducers when I need to subscribe to streams of data and I want to process the data in the stream before using it in my application code. In those cases, I reach for the pipeable operators in RxJS. RxJS pipeable operators behave just like regular transducers, but instead of mapping from reducer to reducer, they map from observable to observable.

Here’s an example from Ramda:

import { compose, filter, map, into } from "ramda"

const isEven = (n) => n % 2 === 0

const double = (n) => n * 2

const doubleEvens = compose(filter(isEven), map(double))

const arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] // into = (structure, transducer, data) => result

// into transduces the data using the supplied

// transducer into the structure passed as the

// first argument.

const result = into([], doubleEvens, arr)

console.log(result) // [4, 8, 12]

Whenever I need to combine a number of operations, such as map, filter, chunk, take, and so on, I reach for transducers to optimize the process and keep the code readable and clean. Give them a try.

Backlinks