Fundamental Math for Game Developers

Math is an important part of game development, and this article discusses how to approach learning math topics such as trigonometry, linear algebra, vectors, matrices, quaternions, discrete math, and calculus & numerical methods. It also provides techniques to improve the way we learn math, such as hiding math between layers of topics we are already motivated to learn. Examples of useful math topics for game developers include vector addition, vector subtraction, vector magnitude, vector normalization, dot product, cross product, matrices, quaternions, and graph theory. Additionally, the article recommends resources such as Coding Math, One Lone Coder, WhyU Animations, 3Blue1Brown, Painting With Maths, and 3D Math Primer for Graphics and Game Development. An interesting takeaway from this article is the "sandwich method" of teaching math, which involves hiding math between layers of topics we are already motivated to learn.

-

Math education should be focused on helping students understand the applications of math in the real world.

-

Understanding the basics of math notation and math jargon is essential for game developers.

-

Vectors and matrices are important for game programming, and understanding dot product and cross product is essential.

-

Quaternions are more compact, efficient, and numerically stable than rotation matrices.

-

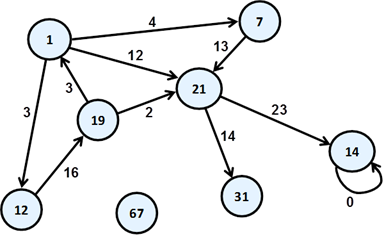

Discrete math is directly related to programming, and graph theory is useful for artificial intelligence.

-

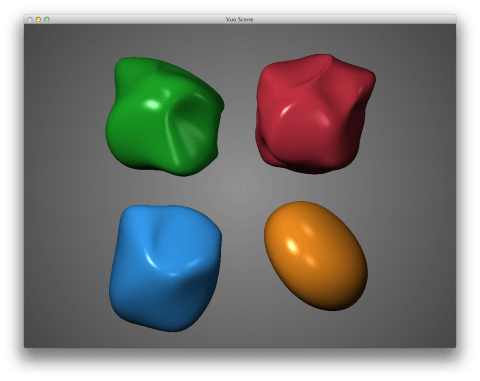

Shaders are used for specialized functions in computer graphics and video post-processing.

-

Calculus, statistics, combinatorics, probability, and information theory are important for machine learning and deep learning.

-

Coding projects are a great way to learn math concepts and develop intuition.

-

The sandwich method is useful for helping students take the first step in learning math.

-

Rigorous math books and resources can help students improve their understanding of math.

The range of mathematics we can use as programmers is quite broad; no single course could cover it. This article is a high-level overview of some of the most important math topics we use as gamedevs. We'll discuss math education, review useful math topics in CS, and present methods we can use to improve the way we learn math.

Programming and mathematics are topics that are very dear to me. I teach math to CS students and every semester I receive a new set of learners that were raised to fear mathematics and doubt their ability to succeed in a college-level math class.

By far, the most common question I get from students is:

"How do I start learning the math I need as a programmer?"

This article will try to answer exactly that! We'll discuss some very important branches of mathematics used by game developers, give examples of where they are applied, and try to put things into context. And as a spoiler, the main math topics we will cover are:

- Trigonometry

- Linear Algebra

- Vectors

- Matrices

- Quaternions

- Discrete Math

- Calculus & Numerical Methods

But I want this blog post to be different than other "math for gamedev" resources out there. Instead of simply being a long bullet-point list of math topics followed by a short paragraph on each, I want this article to be an opportunity for us to reflect.

I want us to think about how we learn new math concepts, mention some of the scars left by traditional math education, and discuss some techniques that helped my students improve the way they study the math they need as developers.

Alright! We have a lot of ground to cover. Let's dive in.

Counting Sparks on Metal

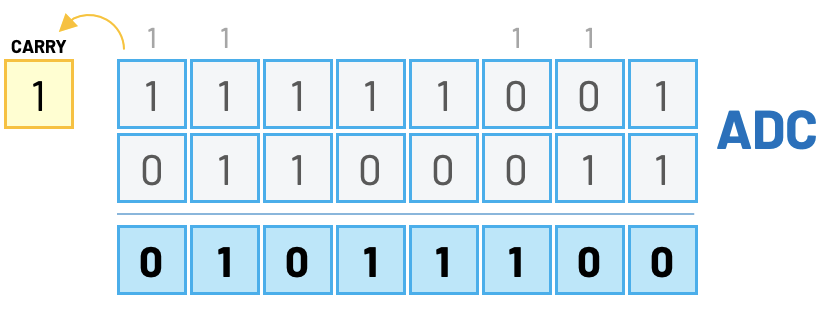

There was a time when the most popular CPUs in the market were only able to add and subtract 8-bit numbers. For something called a "computer", it's surprising that the only two arithmetic operations available on a 6502 CPU were ADC (addition with carry) and SBC (subtraction with carry).

The ADC instruction adds two 8-bit values and sets the carry flag of the CPU.

The family of 6502 microprocessors powered machines like the Atari 2600, the NES, the Apple II, and even the Commodore 64. But regardless of its popularity, the ALU of the 6502 chip was only able to natively add and subtract. If you wanted to multiply two numbers, you had to perform several additions; if you wanted to divide two numbers, you had to use a sequence of subtractions.

LDX #$3 ; X = 3

LDA #$0 ; A = 0

CLC ; Clear carry flag

LOOP:

ADC #$6 ; A += 6

DEX ; X--

BNE LOOP ; Loop back while X != 0

The 6502 code above is a naive way of multiplying 3∗6. At the end, the A register will contain the hexadecimal value $12, which is the same as 18 in decimal. Of course, there were other tricks we could use in some special situations, like bit-shifting values left and right to multiply and divide by powers of two, but you get the idea.

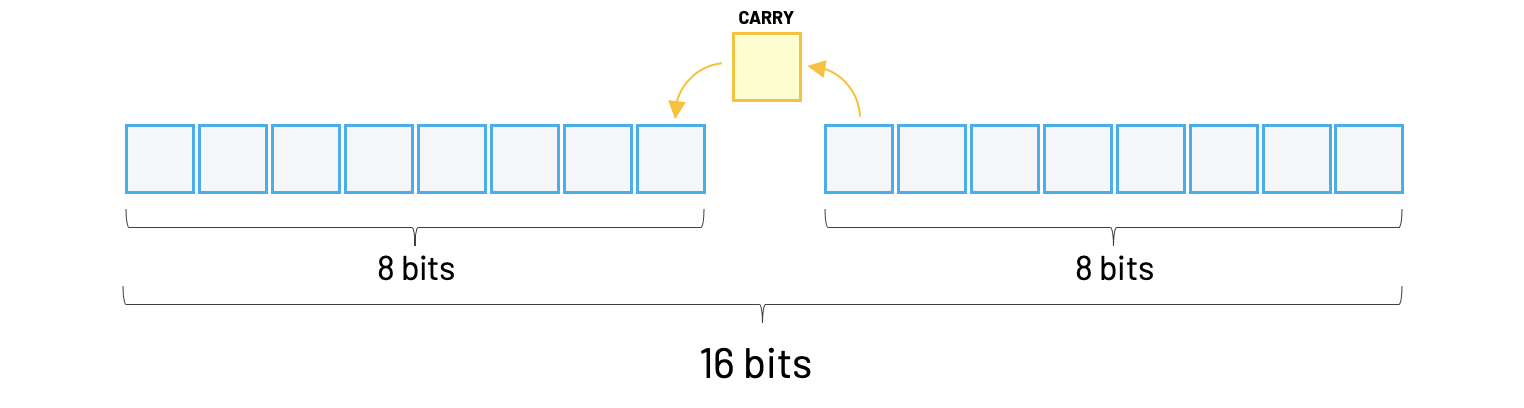

Things get even more complex once we remember we probably need to represent and handle values greater than 8 bits. To represent 16-bit or 32-bit numbers, we had to combine two or more bytes together. That also means we need to worry about carrying the overflow bit of the addition from one byte to the next, or borrowing the lost bit from the subtraction from one byte to the next. Fun times.

Using two 8-bit values to represent a 16-bit number (word) in the 6502

The Motorola 68000 was one example of CPU that already came with native hardware instructions to multiply and divide numbers. The 68000 was the microprocessor powering the Sega Genesis, the Commodore Amiga, and the Apple Macintosh.

For example, the 68000 processor had instructions for MULS (signed multiplication), MULU (unsigned multiplication), DIVS (signed division), and DIVU (unsigned division). These instructions came in handy if you programmed 68000 assembly manually. We no longer had to include long macros in our code just to multiply and divide two numbers.

Fighter Bomber for the Amiga was programmed entirely in 68000 assembly.

Keep in mind that both multiplication and division were incredibly slow instructions on the 68000. Multiplications took between 38 and 70 CPU cycles to complete, while some divisions took around 140 cycles!

Fun fact: Having complex instructions that are able to perform multiple low-level tasks is the philosophy behind the CISC architecture. Some famous CISC chips are the Zilog Z80 and the Intel x86 family of CPUs. On the other hand, RISC chips with a reduced instruction set became very popular. The RISC architecture has a more efficient design, powering many small ARM devices like mobile phones and tablets.

Floats and Precision

And since we are discussing math on old computers, we need to at least mention the topics of floating-point representation, numeric precision, and the struggles of trying to make computers approximately represent real numbers.

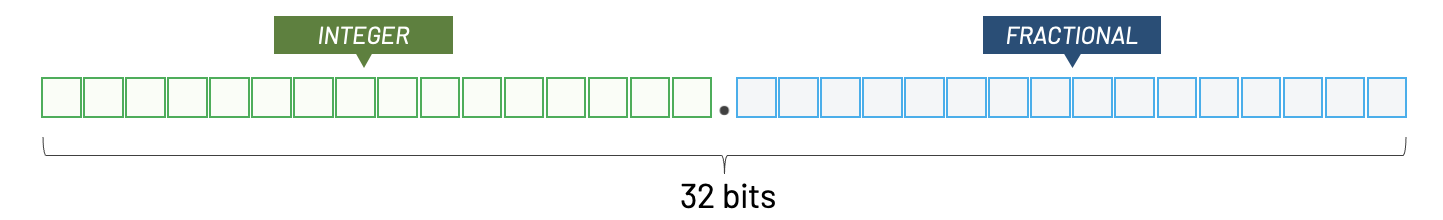

Fixed-point math splits the bits to represent both the integer and the fractional part of a number

Back then, most programs used either integer or fixed-point math. It was not until the late 80s that floating-point systems became popular.

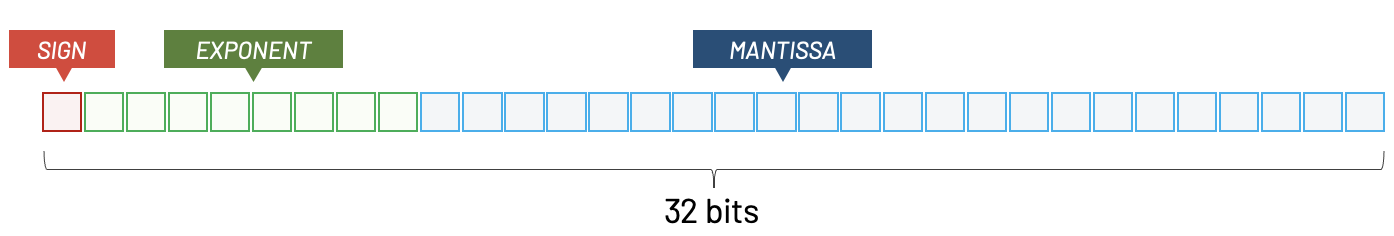

Over the years, a variety of floating-point representations have been used. In 1985, the IEEE 754 standard was established.

Floating-point arithmetic tries to represent real numbers approximately. It uses one bit for the sign, an integer with a fixed precision, scaled by an integer exponent of a fixed base. In a way, we can think of it as the scientific notation we used in school.

(−1)S∗(1.M)∗2(E−127)

The three sections of a floating-point number: Sign, Mantissa, and Exponent.

Floating-point precision issues follow us until today. Since you started reading this article, a new developers out there just learned that floats are not 100% precise in their favorite programming language. Which is why, more often than not, 0.1 + 0.2 != 0.3.

And it's not difficult to get some intuition on why these precision issues happen. Float numbers use 32 bits, allowing us to represent 232 different values. That means we only have 4,294,967,295 (4 billion) different combination of bits to represent the real numbers in our program. Even less, since IEEE 754 reserves some of these values for things like NaNs and infinity.

That's also why increasing the precision to use 64-bit doubles in our code won't fix all our problems. Floating-point numbers are a good option for simple applications that are not precision-critical. Some programmers even suggest using fixed-point instead of floats for applications where precision is a must.

Also, remember that early floating-point systems were extremely slow. For example, the main developer of the 1992 game Comanche: Maximum Overkill, Kyle Freeman, told me that his code used fixed-point math exclusively. In his opinion, the implementation of floating-point numbers on the Intel 386 was simply not fast enough.

Comanche: Maximum Overkill was programmed in 32-bit x86 assembly using fixed-point math.

Doing Less Math

"We were not good at math, but neither were computers. From the moment we arrived at work to the moment we left, the whole goal was to figure out ways to avoid doing math!"

~ John Miles (Origin Systems)

John Miles was a programmer at Origin Systems in the early 90s, developing games like Strike Commander and Wing Commander.

Strike Commander was released by Origin Systems for MS-DOS in 1993

I always loved this quote because it shows how weird the relationship between game programming and mathematics was, specially back then. Machines were extremely limited in terms of performance and numeric precision, and all these constraints meant that the math we used as programmers was often a little bit different than the analytical equations we found in traditional math books.

Game developers live in a constant tug of war. We must find a sweet spot between rigorous math equations and massaging values until our solution looks good enough. Much of what we call game programming relies on cheating and tricking our senses; objects fall, collide, accelerate, fade out, etc. Under the hood, most of these effects are achieved using numerical approximations or simplifications of how reality works.

All those beautiful, continuous, clean, conceptual mathematical models that only exist in our mind need to be translated to ugly discrete sparks on metal.

You will never find a perfect triangle in real life. Perfect mathematical shapes only exist inside our minds.

But as John also points out later in his interview, not doing math can be a challenge.

"...the irony is that we need to know a lot of math to avoid doing math!"

- John Miles

Simplifying formulas and reducing the complexity of a certain algorithm required programmers to be aware of some important mathematical truths. That meant we had to be somewhat comfortable reading obscure articles filled with scary math notation and being able to translate those ideas into fast code.

Let me give you an example. When I teach my students about 3D software rendering, we study something called camera transformation.

A visualization of the OpenGL camera transformation created by Jordan Santell

In a nutshell, we transform all objects in our 3D world by rotating and translating them so they are all positioned in relation to a camera object. At the end, we want a new coordinate system where the origin (0,0,0) is at the original camera eye-point looking at the z-axis.

This camera transformation converts all the points of the 3D scene from one coordinate system (world space) to another coordinate system (camera space).

A transformation like this would normally require us to perform a matrix inversion.

Given two n×n square matrices, A and B, such that:

AB=BA=In

Matrix inversion is the process of finding the matrix B that satisfies the prior equation for a given invertible matrix A and the identity matrix In. In most books, the inverse of A is denoted A−1.

But inverting a matrix is known for being computationally expensive. Having to compute a matrix inverse per-frame would probably be a dealbreaker.

But there's a catch! Since the columns of our matrix encode the base vectors of a coordinate system where the axes x, y, and z are perpendicular to each other, this matrix is orthogonal.

[xxyxzx0xyyyzy0xzyzzz00001]

And if you ever studied linear algebra, you might remember that inverting an orthogonal matrix is as simple as transposing that matrix!

[xxyxzx0xyyyzy0xzyzzz00001]T\=[xxxyxz0yxyyyz0zxzyzz00001]

That's great news. To transpose a matrix, we simply flip it, switching rows with columns. That's objectively a simpler operation than a matrix inversion. This simple trick just saved us many (many!) clock cycles.

Do you see? Just by being aware that the inverse of an orthogonal matrix is its transpose, we were able to convert a problem that was potentially impossible to solve in an older machine now possible.

Cool! So, it looks like some understanding of math was beneficial to programmers, especially in an era where every CPU cycle mattered. But is that still true for the game developers today?

Do Game Developers Need to Know Math?

I was trying to avoid entertaining the controversial "do I need to know math to be a game developer?" question. There are many passionate takes online about this topic already, and I did not want to be yet another blog post adding fuel to the fire. But here we go.

I'll try to be as sober as possible. My short answer to this question is no!

If all you want is to create, publish, and have other people play your game, you can probably do that without any knowledge of advanced math. There are many successful programmers that mention not using any heavy math during the development of their games. So, again, if all you want is to create a simple game and publish it using a modern engine, you probably don't need to know as much math as you think you do.

Of course, this will mostly depend on the nature of your work as a developer. The deeper you dive into game engine code, the more you'll be exposed to fun math topics. If you work creating or maintaining a game engine (rendering, physics, audio, etc.), then you'll benefit from knowing your math.

Game engine programmers are exposed to math topics related to rendering, animation, physics, audio, etc.

But if you are still reading this blog post, I'll assume you already made up your mind and you want to learn more about math. Perhaps you wish to work as an engine programmer in the future, or maybe you just think it's fun and you get a high out of learning new things. Regardless of the why, I won't waste your time trying to motivate you to do something you probably already want to do.

Our Weird Relationship With Math

It's no joke. Programmers are required to constantly keep up with new techniques, acronyms, frameworks, programming languages, and all this new knowledge needs to be absorbed as fast as possible. Therefore, it's only natural that we rely on engines and libraries to perform some of this heavy work for us. We often use libraries as black boxes, assuming (and hoping) that they work correctly by giving us the correct output we need. With deadlines approaching fast, we usually don't bother learning how their internals work or how they were implemented.

Abstraction is a beautiful thing! It is one of the most important pillars of both CS and math, and it's basically what allows us to accomplish great things with software.

For example, we can rely on modern game frameworks to provide helper functions like CastRay(), CrossProduct(), RotateVector(), CheckCollision(), etc. Not only we don't have to worry about how these functions are implemented, but we also benefit from using code that was heavily tested instead of writing things manually and risking adding bugs to our project.

But as helpful as these frameworks and libraries are, we cannot escape from understanding the applications and the actual problem that these functions are solving, the scenarios in which they can be used, and the possible edge cases that might cause them to fail.

Also, what happens when your framework does not provide the exact function you need? Are you confident that the code you copied from StackOverflow really fits the bill? Does it work for left-handed or for right-handed coordinate systems? Does it give the correct results if one of the parameters is zero or negative? What are the units being used?

I noticed that students still struggle to see beyond the API. It's almost like we feel mathematics is something very distant from our coding routine, almost like these math details were something other (smart) people should worry about, but not us.

It's "interesting" how we feel so awkward around math nowadays, given that in the 60s and 70s most research involving computers was conducted by mathematicians. If you were a computer science student back then, chances are you were part of the math department of your university. But CS now became an incredibly diverse and complex field, touching areas like business, engineering, artificial intelligence, biology, health, design, art, education, entertainment, and many others.

Look, I wish I could tell you that my experience with math was different, but it was not. I grew up feeling extremely anxious and hopeless as a math student. I simply did not understand the applications of any of those things I learned in school.

The weird part is that I managed to pass all my exams, memorized all the formulas, and learned how to perform the step-by-step algorithms to get the correct results. But the ugly reality is that I had no idea how to apply any of those concepts outside school. Matrices? Complex numbers? Determinants? Limits? Once again, it all sounded like something other smart people would use in the future, but not me.

Not a fun fact: In a recent Twitter poll, 371 out of 570 participants confirmed that they keep having nightmares about school, including those that completed their education many years ago.

And my history with math would probably end there if it wasn't for an unexpected turn of events. As a CS student, I found myself spending a lot of time hanging out in the math department. That was definitely a surprise! I was lucky to have great math teachers during my first year in college. They helped me see the overlap between some of the CS projects I was working on and the math I was learning in the classroom.

I was encouraged by a teacher to enroll in a class called "History of Mathematics", which helped me put a lot of things into historical context. I was able to understand a little bit better the evolution of the discipline, and that helped me see math through a completely different lens than what I was used to in high school.

Math was also there when I started to feel a little bit disappointed with tech. I felt like some of the things I was learning in of my CS classes were almost disposable. It was like the tech I was studying had an expiration date on it. On the other hand, mathematics felt timeless, and that was extremely appealing to me.

Long story short, I went for a math degree and never looked back!

Why Was I Not Taught This Before?

My first steps into the beautiful world of math was not linear, but it's far from uncommon.

For example, I noticed that many students realize the importance of mathematics only after they start learning more about computer programming.

I was one of these students. I only really understood the appeal of the math I was forced to memorize in high school once I was already an adult studying CS in college. And let me tell you, I was furious about it!

"Why was I not exposed to all these cool applications of math before?"

- angry me from the past

It felt like my entire time in elementary and high school was spent memorizing formulas and blindly performing algebraic tricks that had no connection to what I wanted to do. Finding all these cool examples and applications of mathematics in the world of game programming felt like an ugly betrayal.

Game programming is a great sandbox for visualizing the applications of high-school math.

I was angry at my previous schools, angry at my teachers, but mostly, I was angry at myself. I felt incredibly guilty for wasting my time and for not being mature enough to see how important math was.

If that sound familiar, trust me: you're not alone.

In my years teaching math to programmers, I heard the same story from hundreds of different students.

Maybe what I wrote above does not resonate with you at all. That's probably great news. Maybe you're one of the few lucky students that had great teachers and a great experience learning math in school. If that's the case, yay for you!

The Usual Suspects

Math is present in virtually every class of the standard CS curriculum. For example, machine learning and AI are popular for heavily relying on linear algebra, and students learning about algorithms are often exposed to applications of discrete math, combinatorics, and graph theory.

Given the nature of what I teach, most students that come to me expressing their newfound appreciation for math are usually taking Game Development or Computer Graphics. These two modules are often the ones responsible for igniting that initial spark and bringing my students to the dark side.

Perhaps students were exposed to some simple trigonometry concept as they were trying to move a game object around the screen, or maybe they used some linear algebra trick involving matrices and linear transformations in a computer graphics project. Regardless of how it happens, this feeling is extremely common.

Now What?

Well, there's no point in wasting even more time blaming ourselves or "the system". If we want to get better at math, we have some work to do.

At this point, most students are tempted to:

- Buy as many books as they can on pre-calculus, discrete math, linear algebra, game physics, numerical analysis, etc.

- Subscribe to all the popular math-related channels they can find on YouTube.

- Start downloading lists of exercises from Khan Academy in the hopes of improving their math chops.

Don't get me wrong; these are all amazing tools and many successful students use these resources every day. But you'll be surprised to know that, even after watching all the episodes of 3Blue1Brown and furiously trying out exercises from Khan Academy, most students still don't feel confident in applying that theory in real-world projects.

Pause for a moment and think of all the math books you purchased but never really completed. Maybe you started a math book that looked really promising but you lost the interest and abandoned it after the first chapters? Also, what about all those math videos on YouTube that you started, enjoyed the first two or three minutes because of the cool animations, left, and never returned?

I'm not judging; I've been there. Still, I want to invite you to be honest with yourself and think about the number of math resources that you started and never completed.

So, what's going on here? We know the content is there, right? After all, many reputable institutions and successful students have been using these books. So, why is it that we cannot evolve from reading those math books?

In my experience, some of the reasons are:

- Our lack of experience with math jargon and math notation, which is something most rigorous math books expect from their readers.

- Not enough practical examples, which needs to be something more attractive than problems involving money, percentages, a rolling dice, or decks of cards.

- The temptation of studying advanced topics without having a strong grasp of the fundamentals.

The reasons listed above are not entirely our fault. We just need to find a better strategy if we want to really make the most out of our learning process.

Going Back to the Basics

One of the most important challenges that any beginner math students face is to overcome the temptation of looking at a math problem as just a bunch of symbols and rules. For example, let's look at the property of exponents below:

bn×bm\=bn+m

I'm sure we can all recite this property by heart:

"When multiplying a base raised to one exponent by the same base raised to another exponent, the exponents add."

That's great! But let's pause and try to see beyond the equation. I want us to remember what algebra is all about.

This might seem trivial or too basic to mention, but remember that all these rules and patterns about quantities hold true for any type of object or entity involved. This equation encodes a property that holds true for oranges, cars, ducks, watermelons, and any other discrete entity. And because it's true for any object, we abstract the details and write this relationship using generic letters and symbols.

Look, this is important! Most of us were raised to look at the equation above and simply create links between glyphs and symbols. That's great for when we are trying to be fast and productive, but I want you to force your brain to think about what this property is really trying to tell us. At least until you feel confident you really understood it intuitively.

The example above is extremely simple, but it's surprising how many of us don't stop to really internalize what these symbols on paper really mean. Most "serious" math books will present this type of relationship using math notation; it's up to us to really put in the effort of translating the symbols into something meaningful and create the intuition we need to make sense about what's written on paper.

This distance between symbols and their real meaning is one of the reasons students struggle to digest the contents of resources that use math notation.

If you catch yourself thinking only in terms of rules that you apply on symbols, like when you say "here I can cross x with x", that's when you need to stop and rewind! It does not matter how simple an equation looks, force yourself to find the meaning behind it.

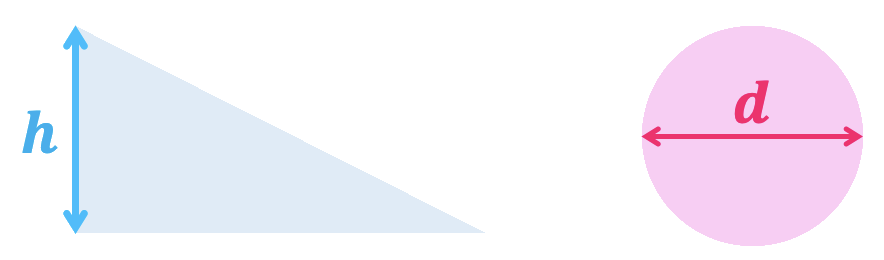

Suggestion: This might seem childish at first, but one technique that really helped me see beyond the symbols and start creating connections to the real meaning of variables was to use different colors as I write math notation. Writing every h in blue and every d in red forces my brain to remember the real meaning of those variables as I derive the equations on paper.

Math Notation vs. Programming Syntax

Besides finding math notation intimidating, programmers also complain that it can be ambiguous. In a world where identifiers must be unique and every semicolon matters, math notation can sometimes throw us a curve ball.

Some example:

- f−1(x) can be an inverse, a preimage, and sometimes even 1f(x).

- f2(x) can be (f∘f)(x) or (f(x))2.

- f(x) is sometimes written as fx, omitting the parentheses.

- sin(x) is sometimes written as sinx, omitting the parentheses.

- sin2(x) is equivalent to (sin(x))2.

- sin−1(x) is equivalent to arcsin(x), and not the multiplicative inverse of sin(x).

Modern programmers are also used to long and descriptive variable names. We think long and hard before giving meaningful names to our variables in code, but most math symbols tend to be dry and short.

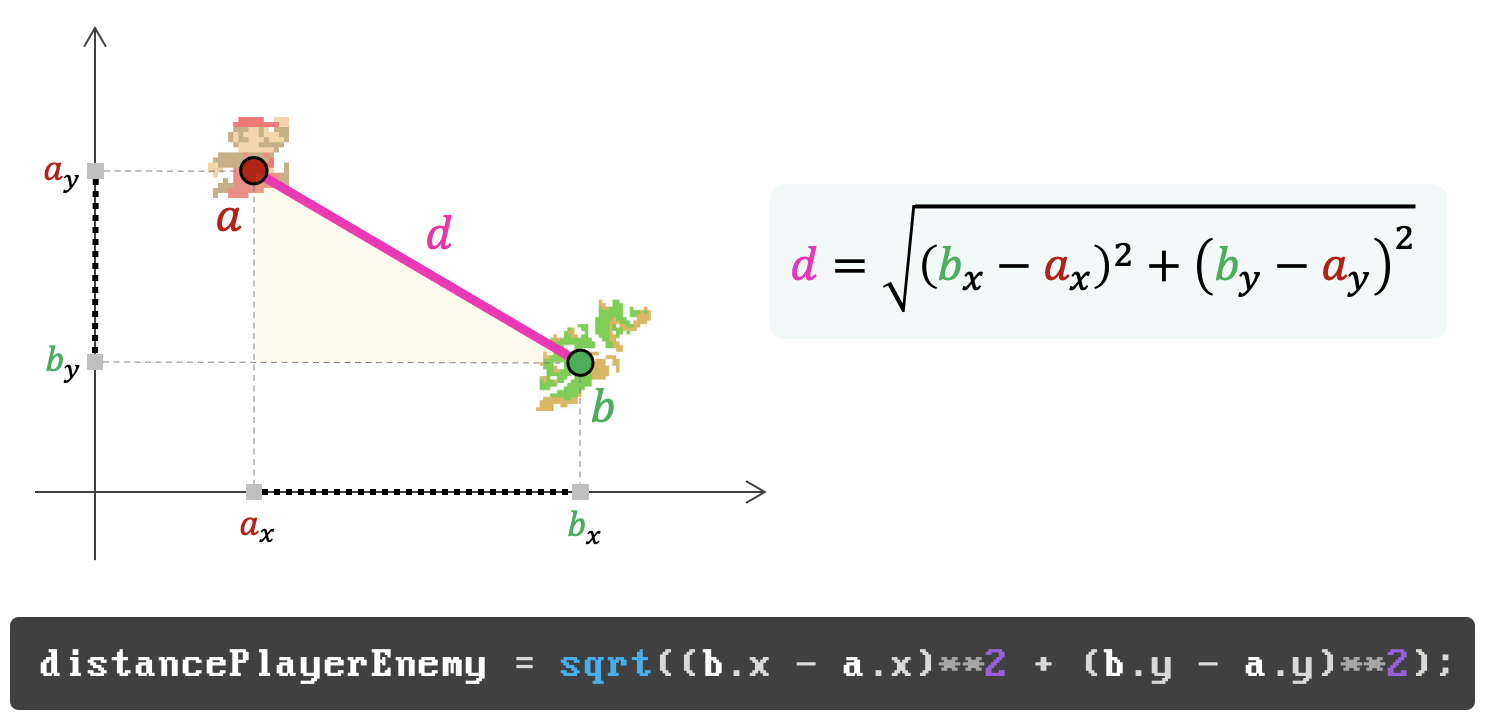

In my opinion, translating math notation to code and using descriptive names is one of the reasons students finally understand the applications of some of the math they saw in the classroom. When we are starting, it's easier to connect the dots if we put things into context. It's a lot more descriptive to name a variable as distancePlayerEnemy instead of just d or, even worse, hypotenuse.

The distance between two cartesian points is the hypotenuse of a right triangle.

Using long and descriptive names does not mean that programming syntax is better than math notation. It simply means mathematicians like to use short and concise symbols; that's all. Keep in mind that math notation was initially developed to be written by hand and most equations tend to get complicated pretty fast. Using verbose names for math variables on a blackboard is probably not a good idea.

Mathematicians prefer to use short variable names so they can expand complex ideas using fewer symbols.

I've also seen programmers create online references translating math notation using code. One of the most popular examples of such translation is the notation used for summations and products.

Capital-Sigma Notation for Summation

The big Greek Σ (Sigma) is for Summation. With whole numbers, we can write it as a loop that sums values.

∑i\=1100(2i+1)

var sum = 0

for (var i = 1; i <= 100; i++) {

sum += 2 * i + 1

}

Here, i\=1 tells us to start at 1 and end at the number above the Sigma, 100. These are the lower and upper bounds, respectively. The (2i+1) to the right of Sigma tells us what we are summing.

The notation can be nested, similar to nesting a for loop. You should evaluate the right-most sigma first, unless the author has enclosed them in parentheses to alter the order. However, in the following case, since we are dealing with finite sums, the order does not matter.

∑i\=1100∑j\=1002002ij

var sum = 0

for (var i = 1; i <= 100; i++) {

for (var j = 100; j <= 200; j++) {

sum += 2 * i * j

}

}

Capital-Pi Notation for Product

The big Greek Π (Pi) is for Product. It is very similar to the Sigma notation, except we are using multiplication to find the product of a sequence of values.

∏i\=110i

var mul = 1

for (var i = 1; i <= 10; i++) {

mul *= i

}

If you want more examples of math notation as code, check out Understanding Math Symbols with Code. Ian Rowan's blog post includes examples on factorials, conditional brackets, and matrix operations.

Careful: Most mathematicians don't like the idea of translating math notation to code, as they are fundamentally different. For example, the assignment operator is not the same as the mathematical equals sign.

x = 0

x = x + 1

From a math perspective, the two lines above are seemingly two declarations of x at odds with each other, and x\=x+1 looks like an equation with no solution.

That is why some schools that teach math using code prefer to use functional programming languages like Racket. These languages avoid these mutations, treating functions, variables, and numbers in a way very similar to mathematics.

Our familiarity with math notation improves as we invite more math into our daily routine. Think of it as learning a new programming language syntax. When we spend 8 hours a day coding in a new language, it slowly becomes second nature.

Before we start looking at important math terms and concepts, I want to briefly talk to you about one technique that helped many of my students improve the way they approach learning new math topics. I call this technique the "sandwich method".

The "Sandwich Method"

I grew up in the south of Brazil, in a corner of the world where the main culture is a mix of different flavors of gauchos from Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina. As you probably know, our diet is heavily based on meat.

As a kid, I always loved everything meat and I hated salad.

Problem: So, how do you make a kid that hates salad eat salad?

Solution: My mom used to hide lettuce leaves inside my sandwiches. I was so happy eating a tasty meat sandwich that I didn't even notice that nutritious lettuce between the many layers of stacked meat and cheese.

Hiding nutritious salad inside layers of tasty meat and cheese.

I apologize for the corny analogy, but you probably know where I'm going with this. I found out that one of the most effective ways of teaching mathematics to a generation of adults that was raised to hate the discipline is to "hide" bits of math between layers of other topics that students are already motivated to learn.

Let's say you want to start learning more about linear algebra and understand some of its applications in game development. You should consider coding a simple programming project that contains some applications of linear algebra in it. It can be a coding project that you are already motivated to complete (that's your sandwich), and the linear algebra required for the game to work correctly is collateral (that's your salad).

We "hide" the math inside a coding project that students are already motivated to pursue.

You know it's good for you. All you need is some help digesting it.

Useful Math Topics for Gamedevs

Very well. Now that we spoke about math education and about learning math, we can start listing some useful math topics for programmers.

There are some branches of math that are particularly important for game developers. Let's briefly mention some of these concepts and I'll also try my best to also add some examples of practical projects that you can use to help you gain some intuition on each topic. These practical projects can be the gentle start you need before you dive deeper into more rigorous material.

Trigonometry

Trigonometry is one of those topics that keep appearing again and again, even in very simple gamedev projects. It's important that most programmers feel somewhat comfortable working with angles and triangles.

You probably learned about pentagons (5-sided polygons), hexagons (6-side polygons), heptagons (7-sided polygons), etc. Trigonometry studies trigons (3-sided polygons), although we tend to simply call them triangles.

This branch of mathematics is concerned with the relationships between angles and ratios of lengths.

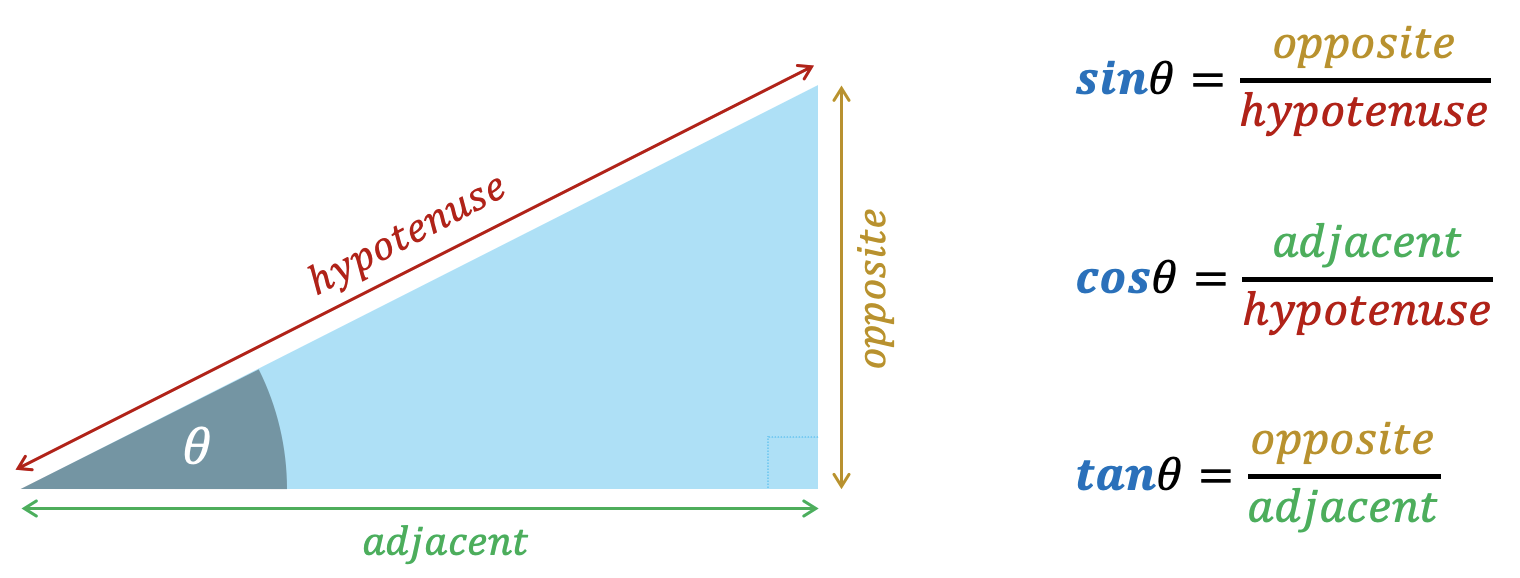

Some people like to use SOH-CAH-TOA to remember the funny names for the sides of a right triangle.

The image below shows the unit-circle and the ratios of the sides of the triangle as our angle grows. The most popular ones are sine, cosine, and tangent.

The sine and cosine in the unit circle. The radius (hypotenuse) has length 1.

I strongly encourage every game developer to learn how sine, cosine, tangent, and arctangent (inverse of tangent) works. There are other important concepts and functions, but these ones should be priority. To hit the ground running, this video from Keith Peters is a good intro to trigonometry with programmers in mind.

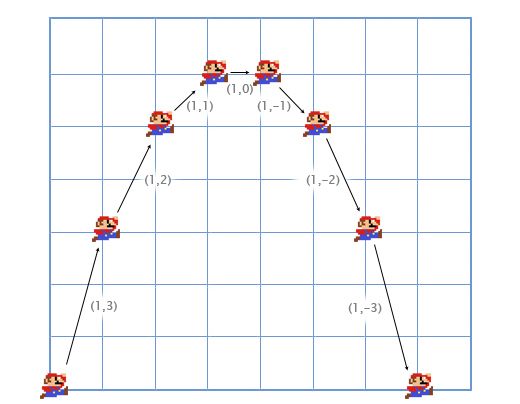

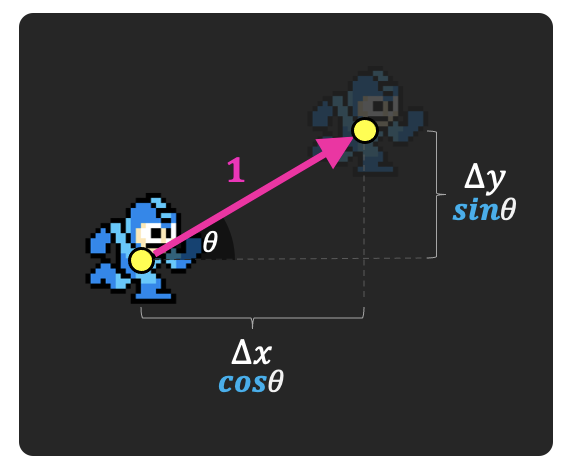

Just to give you an example of a very simple application, imagine that we are storing the x and y position of our player, as well as the angle where the player it's pointing at.

If we need to move our player around the screen at a constant velocity of one pixel per frame, we can use sine and cosine to find the new position x and y that our player will be in the next frame.

Finding the of the player movement from sine and cosine.

Most programming frameworks and trig functions expect angles to be provided in radians (not degrees!). You can visit this short blog post for a quick review of the differences between radians and degrees.

The image above shows how sine and cosine can also help programmers represent oscillation patterns.

There are many examples of games where programmers use these sine and cosine wave functions to visualize the movement of a spring, the swing of a pendulum, and many other types of oscillation effects.

One classic example is the Quake Fluid effect, which uses a sine function to warp texture data. In the original Quake, a fluid surface was simply flat quad with a texture applied to it. But using special values as input for our sine function allows us to create a warp animation effect for the game.

Now, going back to our "sandwich method", I do have some suggestions of practical projects that you can try if you want to improve your understanding of trigonometry.

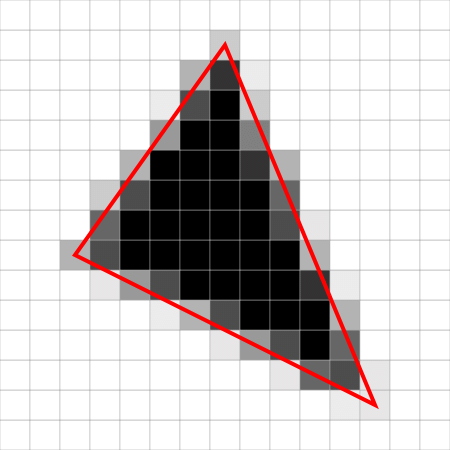

Since we just mentioned Quake, one coding project that contains a lot of trigonometry is to write your own Ray Casting engine. Raycasting is a programming technique that was popularized by an old game called Wolfenstein 3D.

Learn to write a Ray Casting engine from scratch with us.

In a raycasting engine, we cast multiple rays to find the intersection of each ray with objects in a 2D map. Based on the distance of each intersection, we can proceed to project objects on the screen, column per column.

The raycasting algorithm uses the distance of each ray to project and draw wall "columns" on the screen.

This is a super fun project that will require you to work with angles, radians, triangles, trig functions, and many other useful math topics.

Fun fact: Trigonometric functions are known for being computationally expensive, especially in older machines. The original source code of Wolfenstein 3D from 1992 uses look-up tables with pre-computed values of sine and cosine. It's a lot faster to simply fetch the pre-computed values of sine and cosine from an array in memory than having to constantly compute these values at runtime.

Linear Algebra

Most of us had some contact with linear algebra in school, where we were exposed to methods for solving systems of linear equations. But the applications of linear algebra in game development are far from being limited to solving systems of equations. We find linear algebra in computer graphics, physics programming, and many other areas of engine development.

Linear algebra is the part of mathematics concerning vectors, vector spaces and linear mappings between such spaces. We use tools from linear algebra to encode and transform position and orientation of objects in our games.

Vectors

Vectors are the fundamental mathematical objects that are used in virtually every game and game engine. They are very popular in physics to representing quantities that encode both magnitude and direction, like velocity, acceleration, friction, and force.

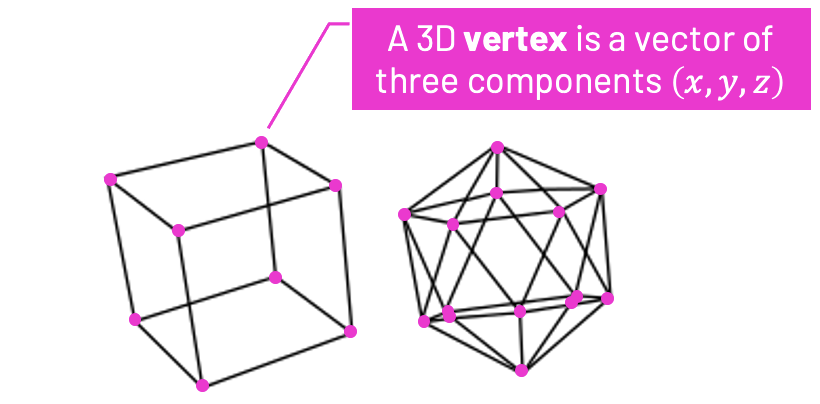

In graphics and physics programming, vectors can be used to define direction, orientation, and also position. These 2D/3D positions are usually stored as vertices.

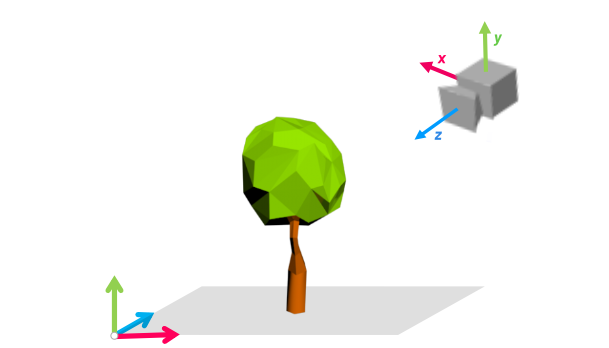

A simple 3D mesh is a collection of vertices (3D vectors) stored in a local coordinate system.

Most vectors we use as a game programmers have two (x,y), three (x,y,z), and in some special occasions, 4 components (x,y,z,w).

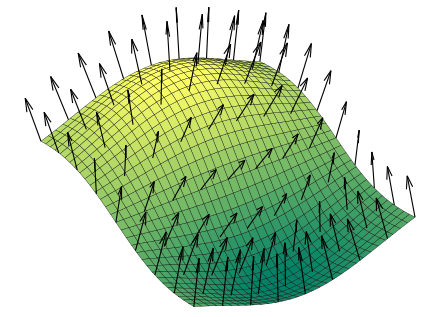

For example, besides storing the vertices of the triangles in a 3D object, we can use vectors to define surface normals. These normal vectors represent the direction where a surface is pointing at. In a 3D model, every triangle of our mesh has a normal vector.

A triangle normal is a vector perpendicular to the triangle face.

Normal vectors help us implement lighting, shading, and triangle culling. In most games, it's beneficial to cull and not render triangles that are facing "away" from the camera.

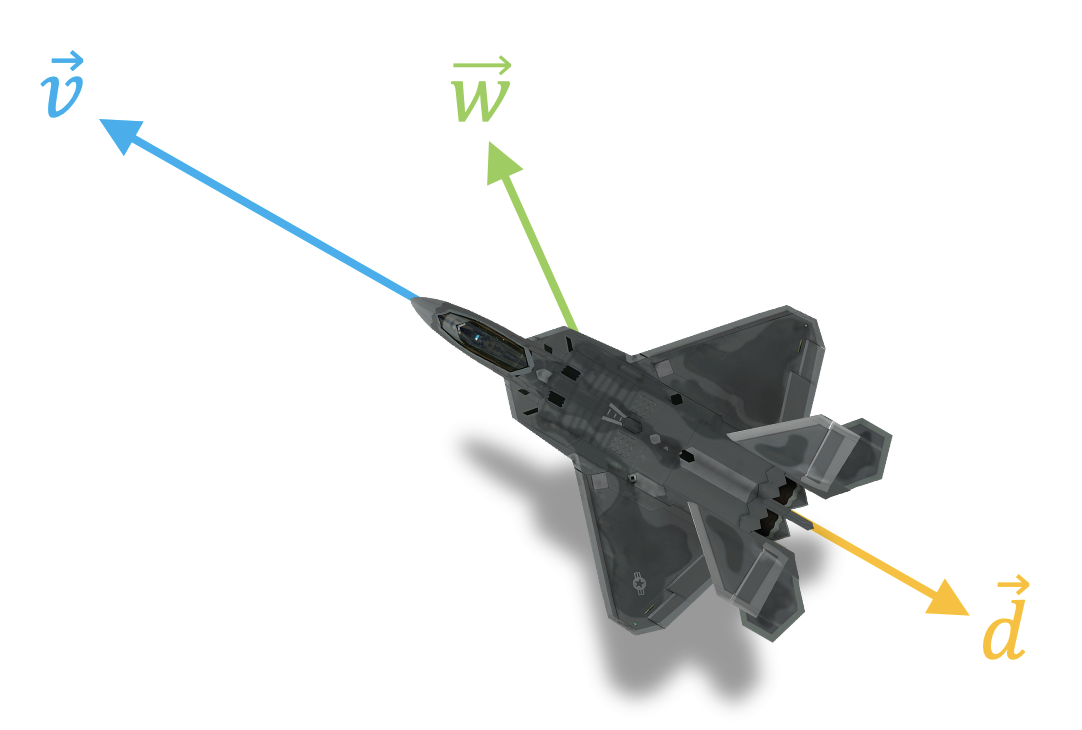

It is no surprise that vectors are also extremely popular in physics simulations. Physics engines usually use vectors to represent vector quantities like position, velocity, acceleration, forces, friction, etc.

Most physics engines use vectors to represent quantities like velocity, friction, drag, force, etc.

As you start your journey learning about vectors, make sure you are comfortable with the following concepts:

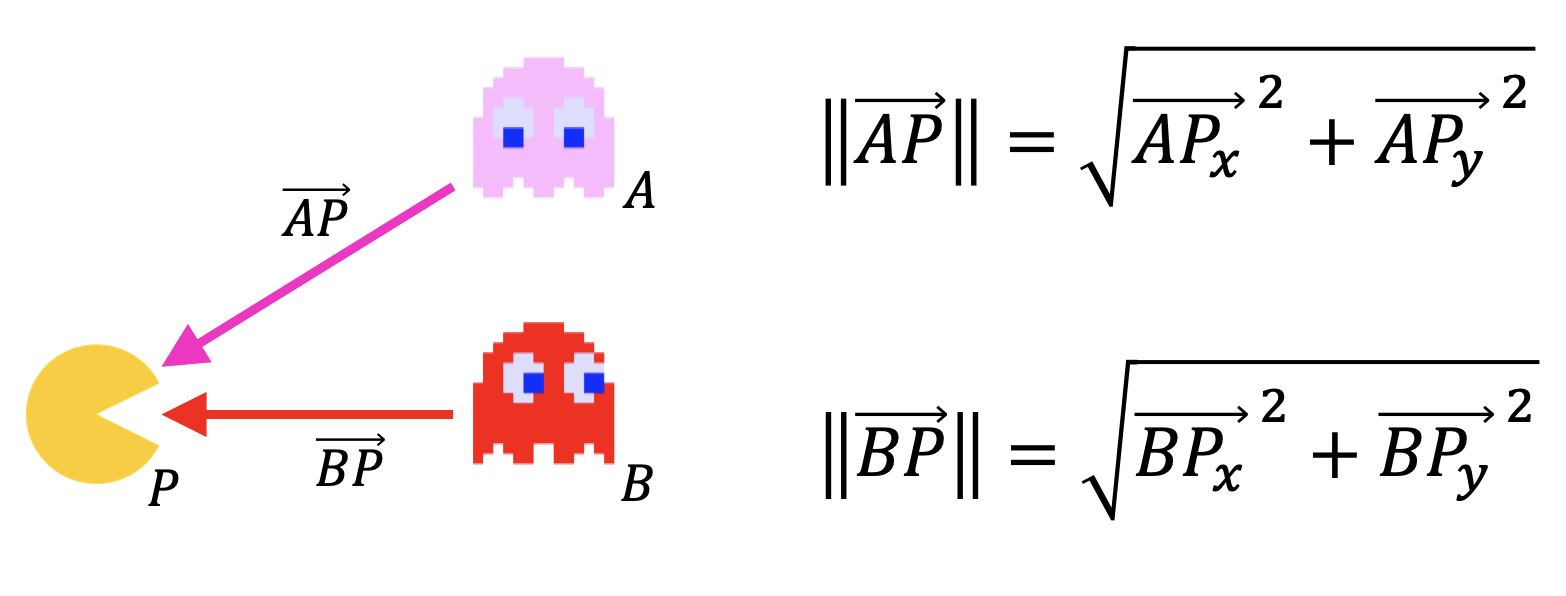

The big names here are dot product and cross product. These vector operations are everywhere in graphics and game programming.

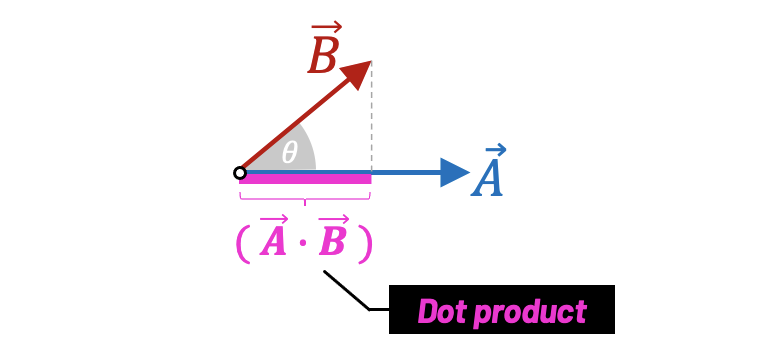

Dot Product

The dot product is sometimes called scalar product because its result is always a scalar.

The dot product (A→⋅B→) has the geometric interpretation as being the length of the projection of B→ onto the unit vector A^.

The result of the dot product is a scalar value.

A→⋅B→\=|A→||B→|cosθ

The dot product is useful when we want to find out how "aligned" two vectors are:

- If both vectors are pointing in the same direction, (A→⋅B→)>0.

- If both vectors are perpendicular to each other, (A→⋅B→)\=0.

- If both vectors are pointing in oposite directions, (A→⋅B→)<0.

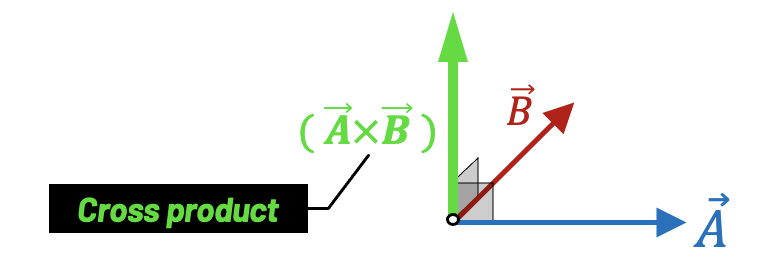

Cross Product

The cross product of two vectors A→ and B→ is another vector that is perpendicular to both vectors A→ and B→.

The result of the cross product between two vectors is another vector.

A→×B→\=|A→||B→|sinθ

Both dot product and cross product are extremely useful for computer graphics, game physics, and overall game programming. There are other important vector operations and transformations, but creating a good intuition on these two should be a priority.

Matrices

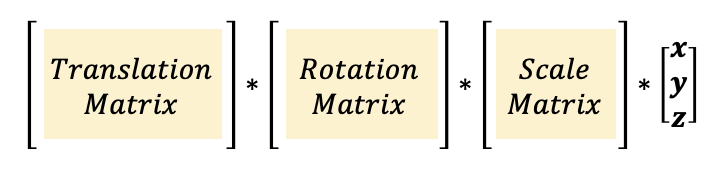

We also use linear algebra to perform special transformations like rotation, scale, and translation. These transformations are often handled by matrices.

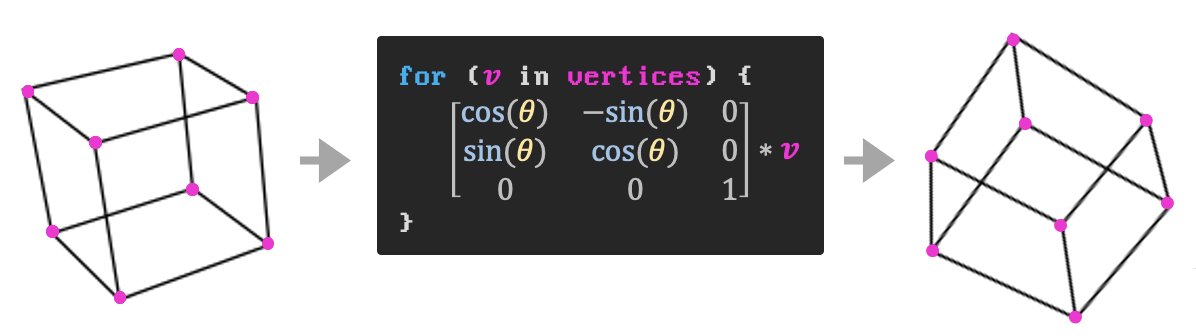

To transform (scale, rotate, and translate) our vertices, we can multiply them by a transformation matrix.

We can have a matrix encode a rotation by a certain angle, and another matrix encoding a translation by a certain offset value. To change the original vertices of a 3D object, we simply multiply the transformation matrix by each vertex/vector of our mesh.

Rotating all vertices/vectors of a 3D model can be handled by a rotation matrix.

It's important to point out is that we can encoded several transformations using one unique matrix instead of separate matrices. We often have one matrix encoding the rotation, scale, and translation of a 3D object.

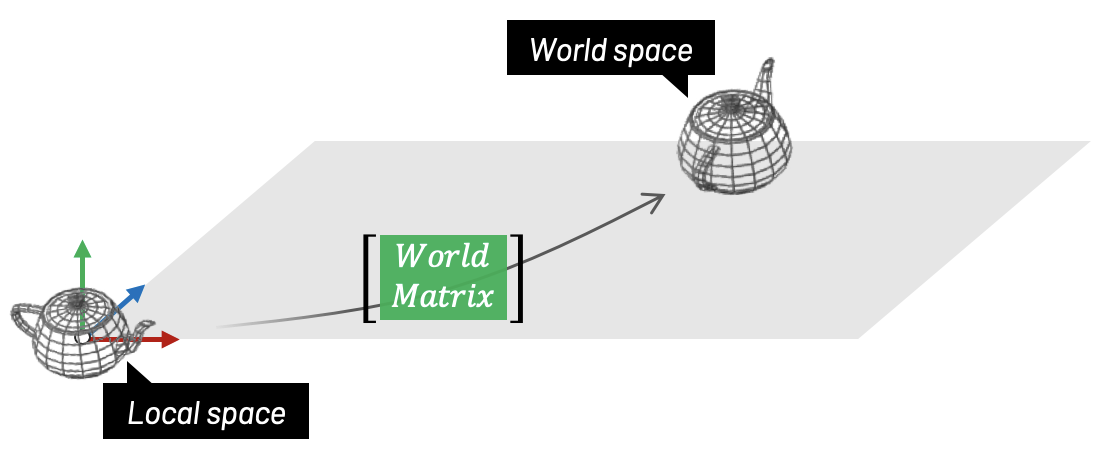

Matrices are also popular for representing changes of coordinate system. For example, when we load a 3D model made by an artist, a lot of the data will be stored in a coordinate system called local space. We need to transform and convert that data into world space.

This conversion from local space to world space means we need to scale, rotate, and translate our object to "place it" in its correct position in the world.

A world matrix scales, rotates, and translates an object, converting it from its local space to world space.

After converting all objects into world space, most game engines will perform something called camera transformation. We already spoke about this transformation, remember? It converts all our objects from world space to camera space. This camera transformation is also encoded using a matrix.

All these transformations and changes in coordinate system from computer graphics are useful for both 2D and 3D games, and they are all handled by linear algebra.

A great project that you can use to learn more about vectors and linear algebra is to code anything related to 3D Computer Graphics Programming. Coding your own 3D software rasterizer, for example, is a great exercise to learn more about the applications of linear algebra in computer graphics. You'll touch topics like vectors, matrices, vertex transformation, projection, and many other important mathematical concepts.

Learn 3D Computer Graphics Programming from scratch with us.

Quaternions

Since we spoke about performing rotations using matrices, it's important to also mention that most modern engines use quaternions to represent 3D orientation.

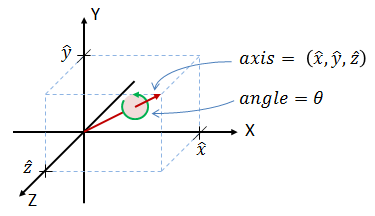

Quaternions provide a convenient mathematical notation for representing spatial orientations and rotations of elements in 3D space. Specifically, they encode information about an axis-angle rotation about an arbitrary axis.

Any 3D rotation can be specified by an axis of rotation and a rotation angle around that axis.

Quaternions are a 4-tuple mathematical object, and they can represent rotation more concisely than matrices.

q\=q0+iq1+jq2+kq3

q\=(q0,q1,q2,q3)

Compared to rotation matrices, quaternions are more compact, efficient, and numerically stable. Compared to Euler angles, they are simpler to compose. Unfortunately, they are not as intuitive and easy to understand. Game engines like Unity provide helper functions for developers to work with quaternions based on angles.

Quaternions also solve some of the issues developers face when using rotation matrices, like gimbal lock. And besides being more robust mathematically than matrices, quaternions also consume less memory and are faster to compute.

Another benefit from using quaternions is that they allow a 3D object to rotate about multiple axis simultaneously, instead of sequentially. For example, to rotate 60 degrees about the XY-axis using matrices, we had to first rotate around the X-axis and then rotate around the Y-axis. With quaternions this sequence of steps is not necessary.

Quaternions are incredibly powerful in game development. They are one example of a mathematical tool that was first described in 1843 and only became popular years later for its applications in computer graphics and engineering. Rotation and orientation quaternions have applications in computer graphics, computer vision, robotics, navigation, molecular dynamics, flight dynamics, orbital mechanics of satellites, and crystallographic texture analysis.

Calculus & Numerical Methods

Calculus is one of those topics that most undergraduate CS students are forced to take during the first year of college.

Most universities squeeze students from different areas into one single big calculus class, which usually means CS students don't get a personalized explanation of the applications of calculus in computer science. Instead, we end up solving problems having to do with measuring the growth rate of bacteria population, heart rate, blood pressure, stock market, etc.

Once again, abstraction is a beautiful thing! The fundamentals we learn in any calculus class should hold true regardless of where we apply them. That said, I noticed that presenting good examples of applications that resonate with students is always a great tool to get them motivated.

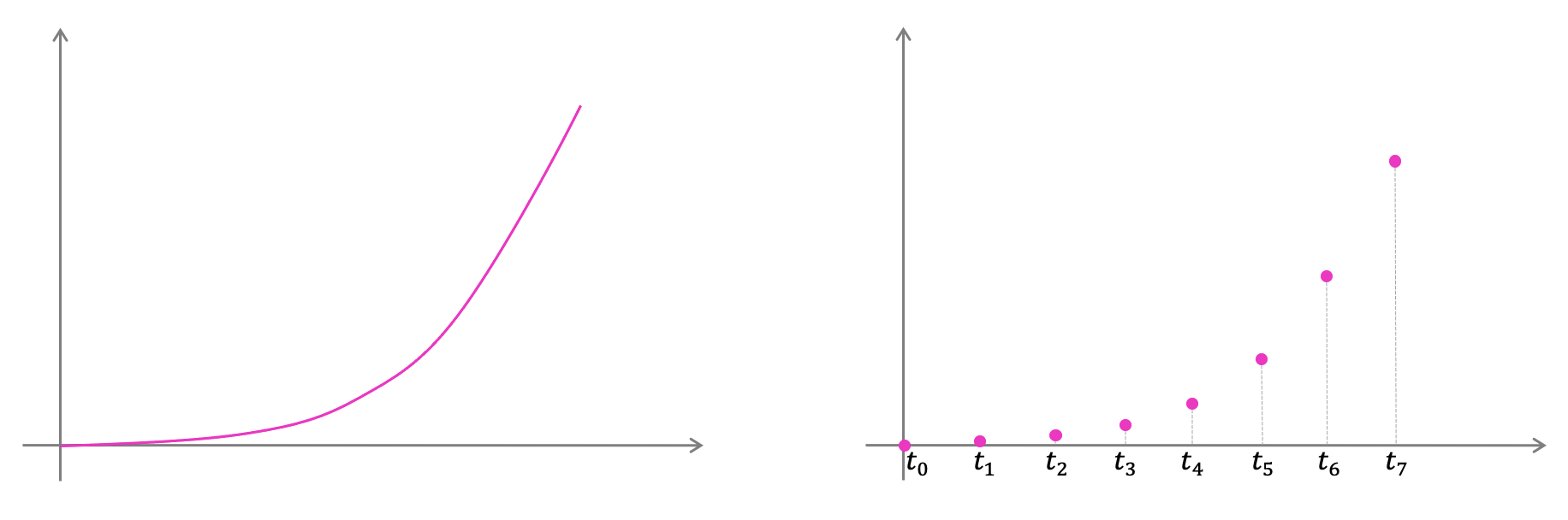

Calculus is concerned with two basic operations, differentiation and integration, and it is used to determine quantities as rates of change and areas. In fact, calculus is the mathematical backbone for dealing with problems where variables change with time or some other reference variable.

Continuous vs. Discrete

Some basic understanding of calculus is essential for any practical engineering problem. But in the case of software, calculus formulas cannot be translated into code without the help of numerical methods.

Digital machines are driven by a clock that ticks at a certain frequency. The clock guides how signals flow in the machine dictating how programs run.

This discrete nature of computers means we cannot deal with problems as if they were continuous. Therefore, we use numerical methods to estimate and find numerical approximations for problems that would have a perfect analytical solution if they were not running on a computer.

A computer needs to sample values at discrete time intervals.

Calculus in Physics Simulation

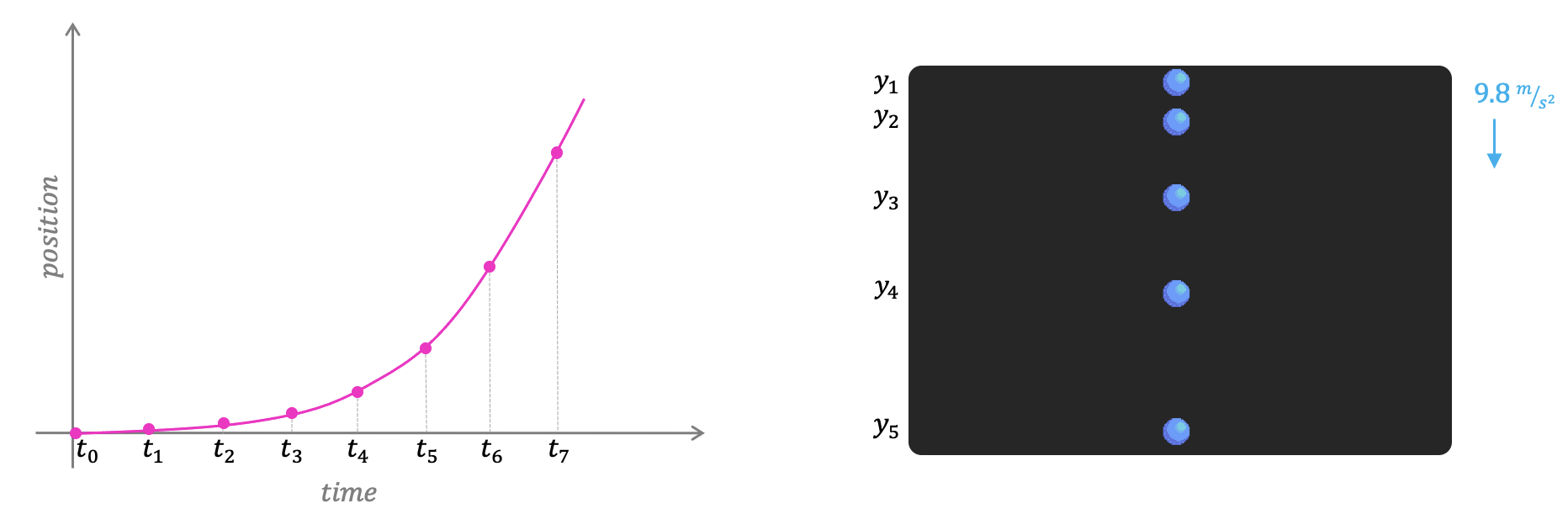

For example, calculus and numerical methods are heavily used inside physics engines. We use integration to compute a numerical estimation of where a game object should be in the next frame based on its previous acceleration and velocity.

Integration helps us estimate the next position based on the object's previous velocity and acceleration.

The video below is a very high-level review of the fundamentals of calculus. It also talks about how these ideas are applied in the simulation of movement in a very simple physics engine.

A super brief review of the fundamentals of Calculus and its applications in simulation of movement.

Calculus in Curves & Shapes

Another example of application of calculus, also related to estimation and rate of change, has to do with defining and rendering curves. Once again, we can think of curves analytically, but there's no fancy math to measure a curve, just discrete samples and estimations. This estimation follows the same idea we spoke above when we were simulating movement. We can measure lines, and if those lines are really small, they get really close to recreating the actual curve.

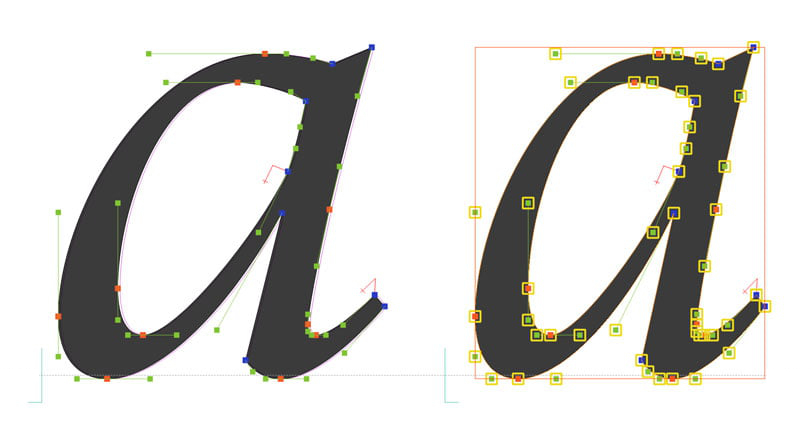

There are many different algorithms for defining curves. These algorithms found their way into computer graphics, game engines, and software in general. Have you ever used the pen tool in Photoshop? Or perhaps wondered how SVGs or TrueType Fonts get perfect curves to be rendered on the screen? These are usually defined using splines. Splines are a mathematical way to produce curves and the cool part is that they are infinitely accurate. The most popular types of parametric curves you'll find in game development are Catmull-Rom, Bézier, and Basis Splines (B-Splines)

TrueType's curves are quadratic B-splines.

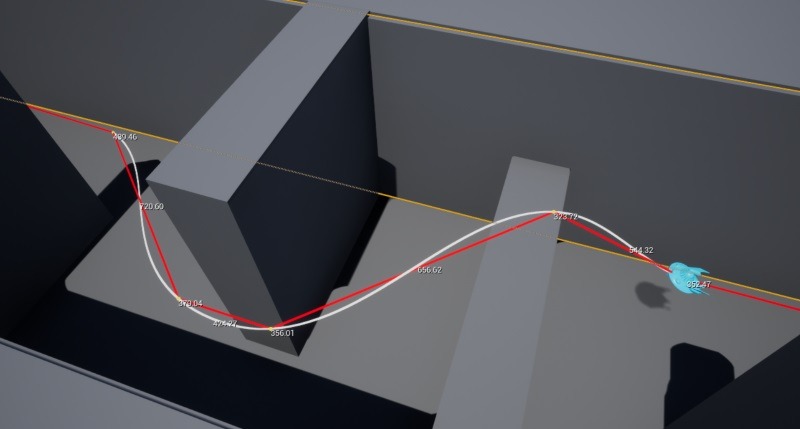

Splines are heavily used by level designers to define paths and curves. For example, we can use splines to determine the path that a camera must follow, or the curves of the road in a racing game.

Splines can define a path for an NPC to follow.

Calculus in Audio & Image Processing

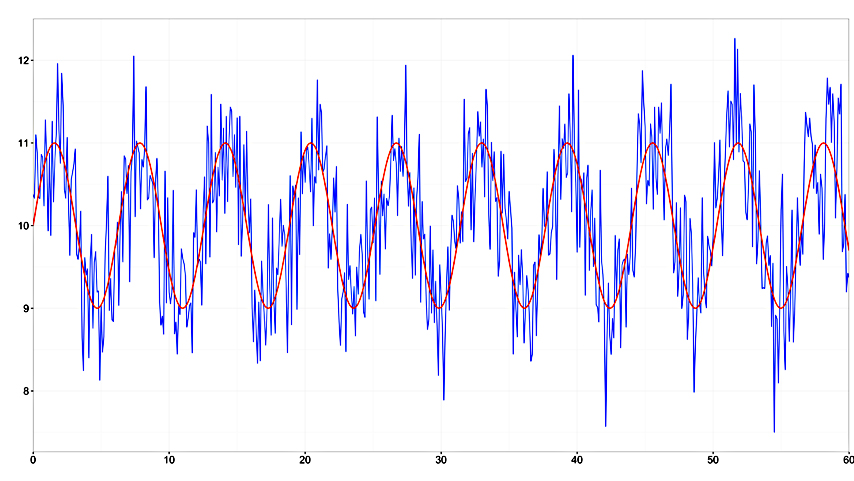

Any type of signal processing is also going to need calculus. Fourier transforms in particular are extremely useful for, say, virtual reality and audio. Any time we have anything that is sampled over time, chances are we'll be using calculus and some flavor of numerical method.

Calculus is used in signal processing applications to filter noise from image and audio.

If you are looking for a practical coding project to learn more about calculus and numerical methods, my recommendation is to learn 2D Physics Engine Programming from the ground up. This project will expose you to topics like integration, vectors, matrices, coordinate-systems, and much more.

Learn 2D Game Physics Engine Programming with us.

Discrete Math

Discrete math is a branch of mathematics involving discrete elements that uses algebra and arithmetic. It is heavily applied in the practical fields of mathematics and computer science. It is also a very good tool for improving reasoning and problem-solving skills.

We'll find applications of discrete math all over in programming and computer science. Not limited to game development, but software applications of logic, sets, graph theory, etc., are extremely important in designing algorithms.

Logic

Mathematics, science, and computer programming are all based on logical reasoning. The better you understand logic, the easier it is to make your games fun, fast, robust, and efficient.

Formally, logic is the study of the principles of valid reasoning and inference. As game programmers, our goal is telling the machine exactly what to do in any possible scenario. We do that by using logic. Game development logic is based on mathematical logic, and propositional logic is the basic building block of our design. It should be no surprise to all readers that conditional statements, like if-else, are directly based on propositional logic.

Set Theory

Set theory is the branch of mathematics that studies sets, which are collections of objects, such as {blue, white, red} or the (infinite) set of all prime numbers. Although we can't represent infinity with computers, in theory sets can have an infinite number of elements. In our case, there's always memory size and disk space to set hard boundaries of how many elements our sets can contain.

There are many data structures that programmers use that are based on set theory. Dealing with collections and sets of discrete objects is a very common task in the day of a programmer.

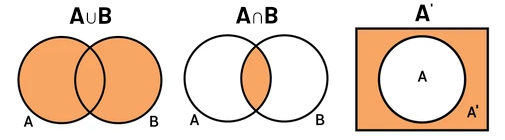

Relational databases and how they handle records are an example of set theory in action. Databases use concepts from set theory to define operations like union, intersection, complement, etc.

A Venn Diagram representation of the union, intersection, and complement of sets A and B.

Graph Theory

As you can see, discrete math is directly related to programming in general, and game developers must be comfortable with these ideas in order to design and implement algorithms.

Another topic of discrete math that is extremely useful in computer science is Graph Theory, which studies graphs and networks. Graphs are one of the prime objects of study in discrete mathematics. They are among the most ubiquitous models of both natural and human-made structures. They can model many types of relations and process dynamics in physical, biological and social systems. In computer science, they can represent networks of communication, data organization, computational devices, flow of computation, etc.

Graph theory has many applications in programming and system design.

A good and beginner-friendly resource on the applications of graph theory in CS is Clara Nguyễn's talk on the applications of graph theory in video games.

A.I.

One special mention before we go is artificial intelligente and the math that underpins it.

A.I. has been an integral part of video games since their inception. In most video games, artificial intelligence is used to generate responsive, adaptive or intelligent behaviors primarily in non-player characters (NPCs) similar to human-like intelligence.

An example of an A.I. model that helps game characters learn how to move by imitating motion capture clips.

Some of the math used in the field of A.I. was already mentioned before. Linear algebra is on the top of the list of topics heavily used by game A.I., including vectors, matrices, and tensors.

The deeper we dive into the world of A.I., touching the topics of machine learning, deep learning, natural language processing, etc., the more we are exposed to important applications of calculus, statistics, combinatorics, probability, and information theory.

Shaders

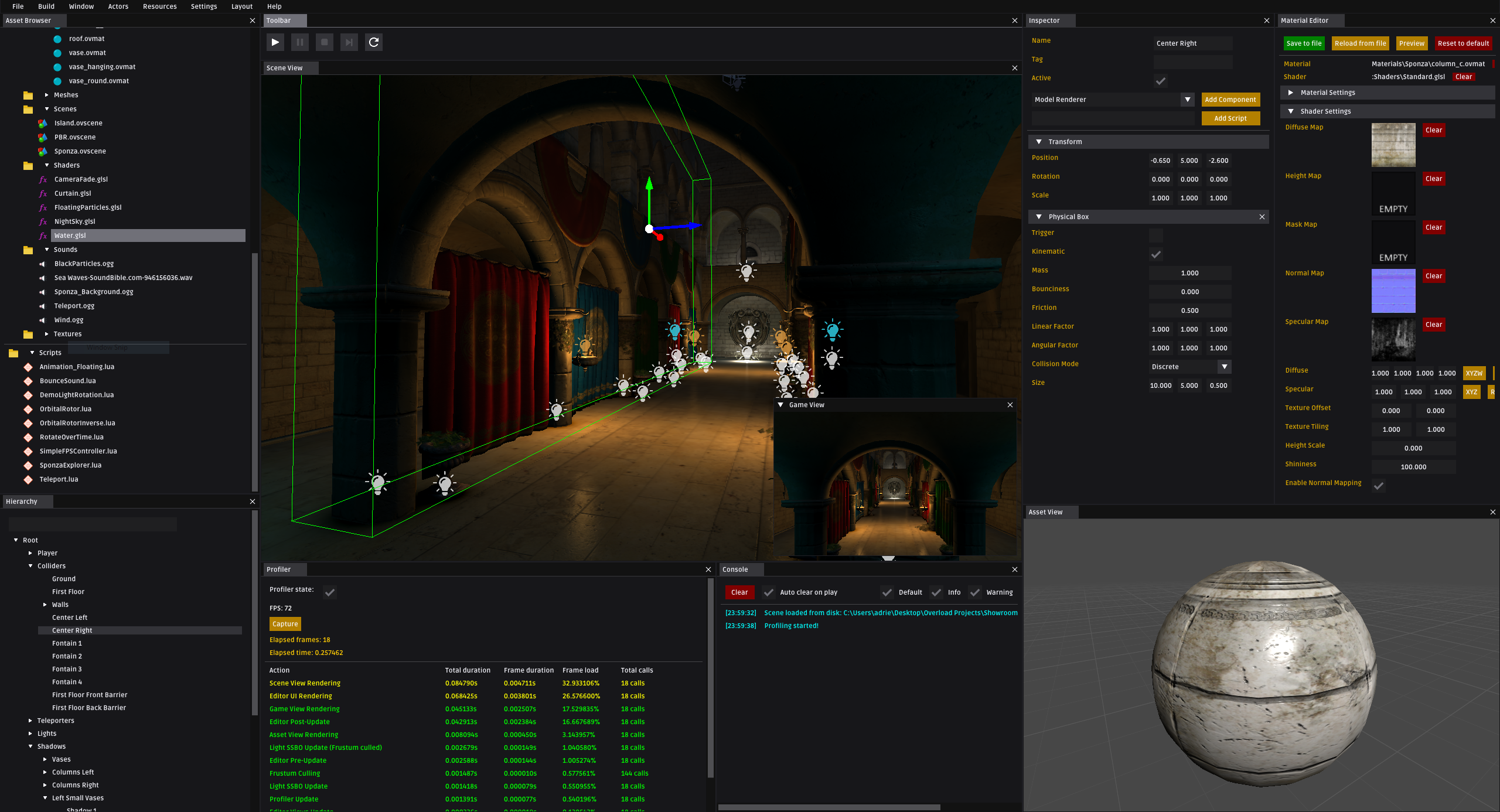

Another huge area where mathematics is important is in developing shaders. A good understanding of vectors, matrices, and trigonometry is a must for shader programmers.

Shaders calculates the appropriate levels of light, darkness, and color during the rendering of a 3D scene. Shaders have evolved to perform a variety of specialized functions in computer graphics special effects and video post-processing, as well as general-purpose computing on GPUs.

Shaders are commonly used to produce lit and shadowed areas in the rendering of 3D models.

Recommended Resources

We mentioned several math topics and discussed some very important ideas about math education and techniques on how to approach learning math.

I also want to leave some of my favorite resources on math for programmers. These are mostly resources for beginners and they try to follow that philosophy of the "sandwich method" of using practical projects to teach important concepts of mathematics.

Nature of Code (Daniel Shiffman)

This is one of my favorite books out there. It is not directly about mathematics, but it definitely fits the bill in terms of using practical coding projects to teach important math concepts.

Nature of Code by Daniel Shiffman

Coding Math (Keith Peters)

Coding Math is an ongoing series of video tutorials designed to teach you the math you need to understand as a programmer. Keith Peters recorded this series to help programmers that often stumble on the mathematics they need to use to achieve various visual effects, motion, etc. Coding Math helps explain these in a clear, easy to understand way, with real world code you can use in your own projects.

Coding Math YouTube channel by Keith Peters

One Lone Coder (David Barr)

Best known by its YouTube user name, Javidx9, David Barr is one of my favorite content creators. His channel is great when it comes to mixing coding projects with applied gamedev math. David picks small gamedev ideas and explains the math that makes them possible.

OneLoneCoder YouTube channel by Javidx9

WhyU Animations (Steve Goldman & Mark Rodriguez)

If you are looking for a place to help with improving your intuition on basic math concepts, WhyU animated videos might be the thing for you. Rather than focusing on problem solving, the objective is to give insight into the concepts on which the rules of mathematics are based.

WhyU animations by Steve Goldman & Mark Rodriguez

3Blue1Brown (Grant Sanderson)

Iit would be really weird not mentioning Grant Sanderson's YouTube channel in my list of recommendations. It is definitely a must for anyone interested in math. Following the same idea of WhyU videos, 3Blue1Brown is a good option for those who want to develop an intuition for basic math topics.

3Blue1Brown YouTube channel by Grant Sanderson

Painting With Maths (Inigo Quilez)

This one is a little more advanced, but equally interesting. Inigo has a series of resources where he teaches how to write shaders and output images only using math.

Painting a Character With Maths by Inigo Quilez

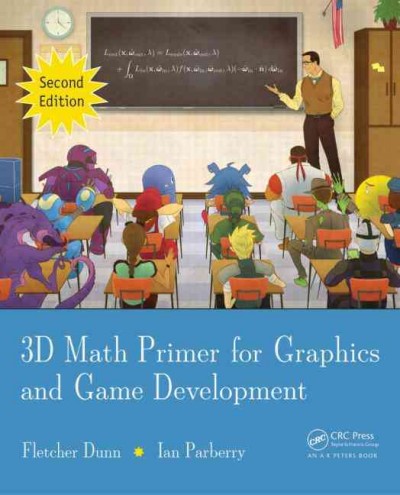

3D Math Primer for Graphics and Game Development (Fletcher Dunn)

If you are a beginner, this is a very good book with many examples of applications of mathematics in game development. It's one of the few books I recommend for those students that are just getting their feet wet with CS and mathematics. The book can be accessed free online, but I strongly encourage supporting the author.

3D Math Primer for Graphics and Game Development by Fletcher Dunn

Conclusion

There you go! We have covered a lot of ground and touched several important ideas from mathematics that are useful to game programmers.

I hope you enjoyed this discussion on the applications of mathematics in the world of computer science and game development. As you can see, depending on the type of work you'll be responsible for, you might be exposed to more or less math.

It goes without saying that what we covered here is an extremely high-level overview. It would be naïve to think we could cover each topic in depth.

Limitations of the "Sandwich Method"

The sandwich method was the topic of my master's thesis back in 2018, although I did not call it that when I was writing my paper. The study shows an improvement in the understand of basic math topics when they are put into context in form of a practical project. The control group used traditional methods, such as text-based articles and book exercises.

Keep in mind that, using a practical project to put a theory into practice is helpful but it will not cover all the material and it won't make you an expert on the topic. As you finally start connecting the dots and removing the fear of both math notation and math jargon, the next natural step is to find more rigorous material and grow from there.

The sandwich method is useful in helping you take that important first step. I noticed that it's a lot easier for students to consume other math resources after this first step.

Why Reinvent the Wheel?

It's worth mentioning that many of the topics and concepts we discussed are already being provided by your prefered game engine. Engines like Unity and Unreal already implement most of the ideas we spoke, and all we need to do is use them. We don't need to worry too much about the type of numerical integration Unreal's physics engine uses, or how quaternions are being represented under the hood by Unity.

Also, you probably noticed that my examples are usually related to engine development and low-level implementation of programming concepts. Some people argue that I'm encouraging students to "reinvent the wheel" and that is counterproductive. I understand the claim and I take full responsibility for my approach. I strongly believe that learning and being aware of the low-level details of how things work is extremely eye-opening to every serious game programmer.

"There's nothing wrong in reinventing the wheel if your goal is to learn more about wheels."

- David Barr (OneLoneCoder)

Great stuff! If you think I forgot to mention something important or if you have any suggestions for this article, you can follow me on Twitter and send me an angry message there. But if you learned at least one interesting thing reading my blog post, then I guess the whole thing was worth it.